The Spirit of Mysticism

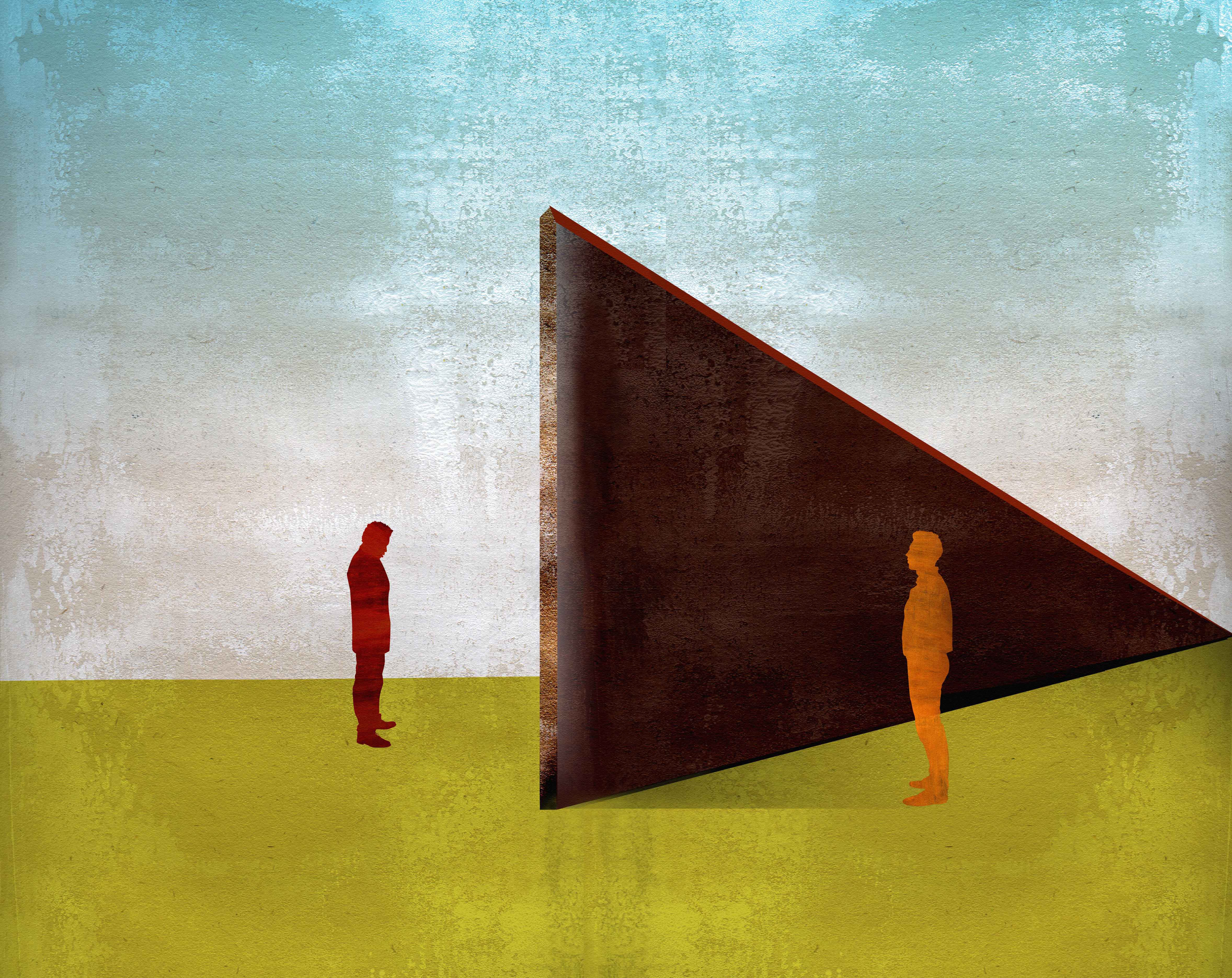

Apart from the Quran, I mainly studied the form of Islamic mysticism called Sufism. Mysticism sounds like something marginal, esoteric, a kind of underground culture. But nothing could be further from the truth when it refers to Islam. Until the 20th century, Sufism was the basis of popular piety almost everywhere in the Islamic world. It remains so to this day in Asian Islam.

Islamic high culture, especially poetry, the visual arts and architecture, was also permeated with the spirit of mysticism. As the most common form of religiosity, Sufism formed an ethical and aesthetic counterweight to the orthodoxy of the Islamic jurists. By emphasising God’s mercy, by looking behind every letter of the Quran, by always seeking beauty in religion, by recognising truth in other forms of faith as well, and by explicitly adopting the Christian commandment to love one’s enemies, Sufism permeated Islamic societies with values, stories, and sounds that could not have been derived from the kind of piety that followed Islam to the letter. Sufism as lived Islam did not abrogate legal Islam but complemented it, made it softer, more ambivalent, more permeable, more tolerant in everyday life, and made it possible to experience it sensually through music, dance, and above all poetry.

Barely a trace of it remains. Wherever the Islamists gained a foothold, starting as early as the 19th century in what is now Saudi Arabia and ending in Mali, they began by putting an end to Sufi festivals, banning mystical writings, destroying the tombs of the saints, and cutting off the long hair of Sufi leaders or even killing them outright. But not only the Islamists. Even the reformers and proponents of religious enlightenment of the 19th and early 20th centuries considered the traditions and customs of folk Islam to be backward and outdated.

All over the Islamic world, the destroyed, disregarded, scruffy old cities with their dilapidated monuments are as much symbols of the decay of the Islamic spirit as the world’s biggest shopping mall that has been built right next to the Kaaba in Mecca.

They were not the ones who took Sufi writings seriously. Rather, it was Western scholars, Orientalists such as the 1995 Peace Prize winner Annemarie Schimmel, who edited the manuscripts and thus saved them from destruction. And even today, very few Muslim intellectuals engage with the richness that lies in their own tradition. All over the Islamic world, the destroyed, disregarded, scruffy old cities with their dilapidated monuments are as much symbols of the decay of the Islamic spirit as the world’s biggest shopping mall that has been built right next to the Kaaba in Mecca. This has to be kept in mind, and photos also clearly show how the holiest place of Islam, this simple yet magnificent structure where the Prophet himself prayed, is literally dwarfed by Gucci and Apple. Perhaps we should have listened less to the Islam of our great thinkers and more to the Islam of our grandmothers.

Of course, some countries have begun restoring their buildings and mosques, but it took Western art historians or even Westernised Muslims like me to come along and recognise the value of tradition. And, unfortunately, we were a century too late. The buildings had already crumbled, the construction techniques were forgotten, and the books erased from memory. But we still thought we had time to study things thoroughly.