Brutal Spending Cuts

Many are also planning brutal spending cuts. Oxfam has calculated that over the next five years, three-quarters of governments are planning to cut spending, with the cuts totaling $7.8 trillion dollars. An age of crisis, creating huge fortunes for a tiny few. Meanwhile, the scale of wealth being accumulated by those at the top, already at record levels, has accelerated. The global polycrisis has brought huge new wealth to a tiny elite.

Over the last 10 years, the richest 1% of humanity has captured more than half of all new global wealth. Since 2020, according to Oxfam analysis of Credit Suisse Data, this wealth grab by the super-rich has accelerated, and the richest 1% have captured almost two-thirds of all new wealth. This is six times more than the bottom 90% of humanity. Since 2020, for every dollar of new global wealth gained by someone in the bottom 90%, one of the world’s billionaires has gained $1.7m.”

The common challenge we are facing, is that we are destroying our planet for the profit of the few, and this represents a global catastrophe. We do not lack resources to face them. World GDP reached around 100tn dollars in 2022, which is equivalent to 4,200 dollars per month per four-member family. We can use Net National Income or other variations, but the basic fact is that with a very moderate reduction of inequality, we can ensure everyone has access to the material dimensions of a dignified life.

Latin America, the most unequal region in the world, is preparing a major event on this issue for July 2023. But then again, with global asset-management corporations dominating the financial system, virtual money and tax havens, regional solutions are limited: Tax abuse by multinationals and the richest in our societies has developed in the context of globalization and requires global solutions. But it also needs a Latin American perspective that defends the interests and characteristics of the region.

Basic fact is that with a very moderate reduction of inequality, we can ensure everyone has access to the material dimensions of a dignified life.

With the first Latin American and Caribbean tax summit in Colombia, which has the title, “Towards an inclusive, sustainable and equitable global taxation”, the Andes State can now make history to ensure that the countries of Latin America and the Caribbean go further together and define more effective mechanisms in the fight against tax avoidance, both by large corporations and large wealth holders. This can also ensure that the region joins forces to shape the international agenda.

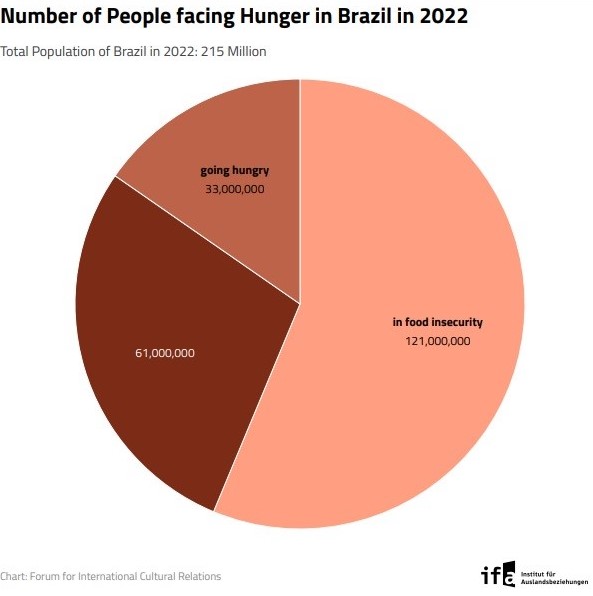

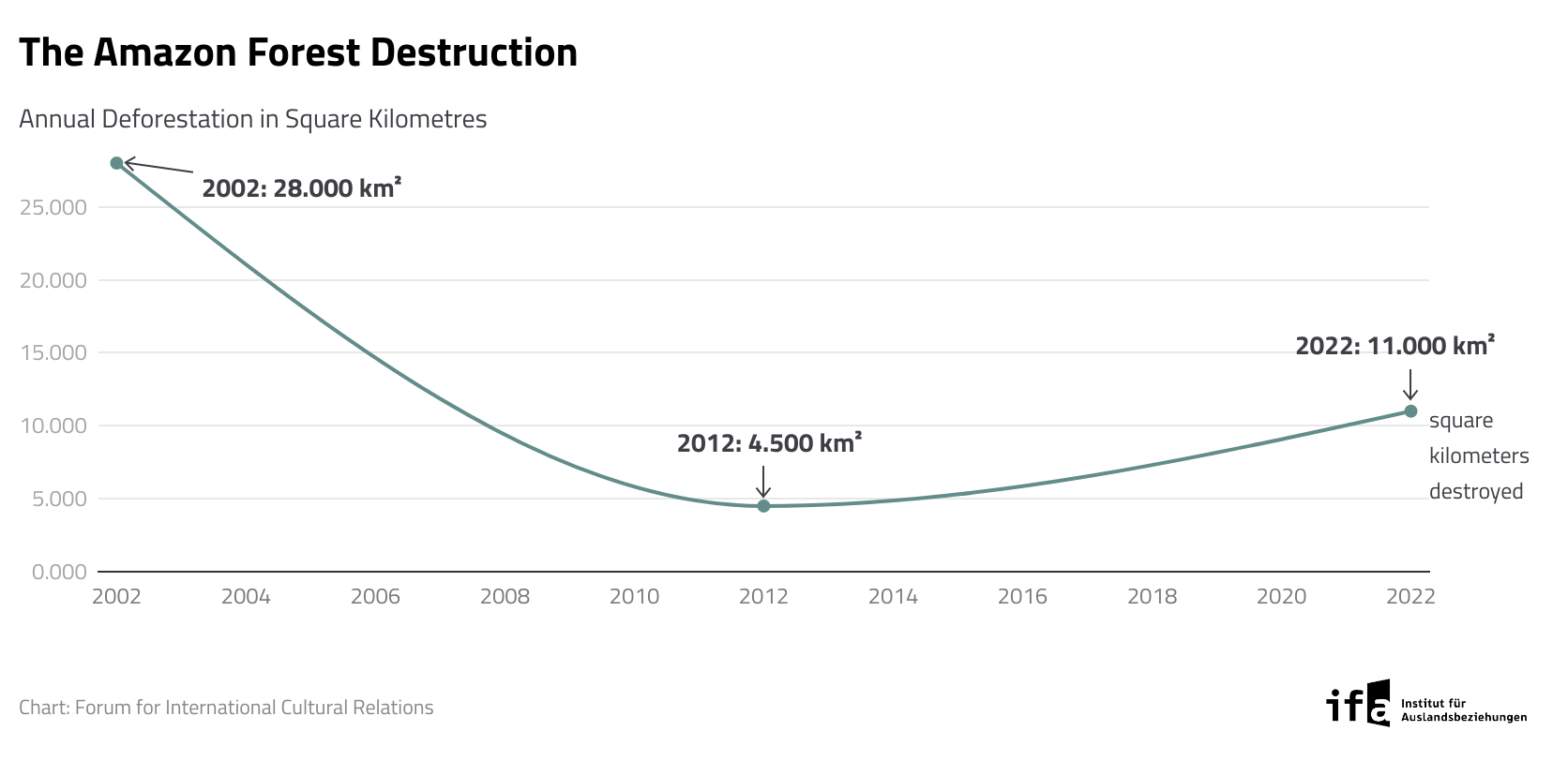

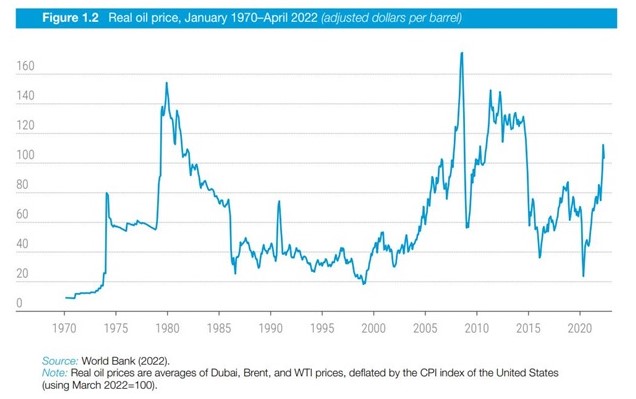

We are looking here at key challenges, access to food and energy, environmental impacts, inequality, and the structural deformation of the financial system, through which our money, instead of funding the necessary measures to ensure sustainable development, generated a global rentier extractive economy.

The dimensions of this challenge can be seen for example in the fact that BlackRock, a private asset-management corporation, manages 10tn dollars, while Biden manages a federal US budget of 6tn. In Brazil, the right-wing government managed to transfer the Central Bank control to private banks, generalizing usury, and reducing 79% of families to unsustainable indebtedness and paralyzing the economy.

Facing global finance with national initiatives simply does not work.

European banks operating in Brazil gladly accepted usury: Santander sent millions of messages to would be clients presenting an “opportunity”: “Excellent news for moment of hard times! Interest rate on your account limit fell to 5.9% per month, until 31/01/2023”. I received this message on my cell phone, and obviously few people understand that a monthly rate of 5.9% is equivalent to practically 100% a year. I am presenting this personal note because few people believe that a modern European bank can resort to this level of usury in other countries.

We are looking here at key challenges, access to food and energy, environmental impacts, inequality, and the structural deformation of the financial system.

Controlling finance, making it useful for the economy again, is a global challenge, as the Base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) negotiations show, and a key area of international collaboration. BEPS refers to tax planning strategies used by multinational enterprises that exploit gaps and mismatches in tax rules to avoid paying tax. Working together within OECD/G20 over 135 countries and jurisdictions are collaborating on the implementation of 15 measures to tackle tax avoidance, improve the coherence of international tax rules and ensure a more transparent tax environment.

![[Translate to english:] Foto des Amazonas und darüber liegt der Schriftzug: "Is A Decolonial Climate Foreign Policy Even Possible?"](/fileadmin/Content/images/mediathek/blog/Forum_Blog/ifa-forschungsprogramm_is-a-decolonial-climate-foreign-policy-even-possible_videostill.png)