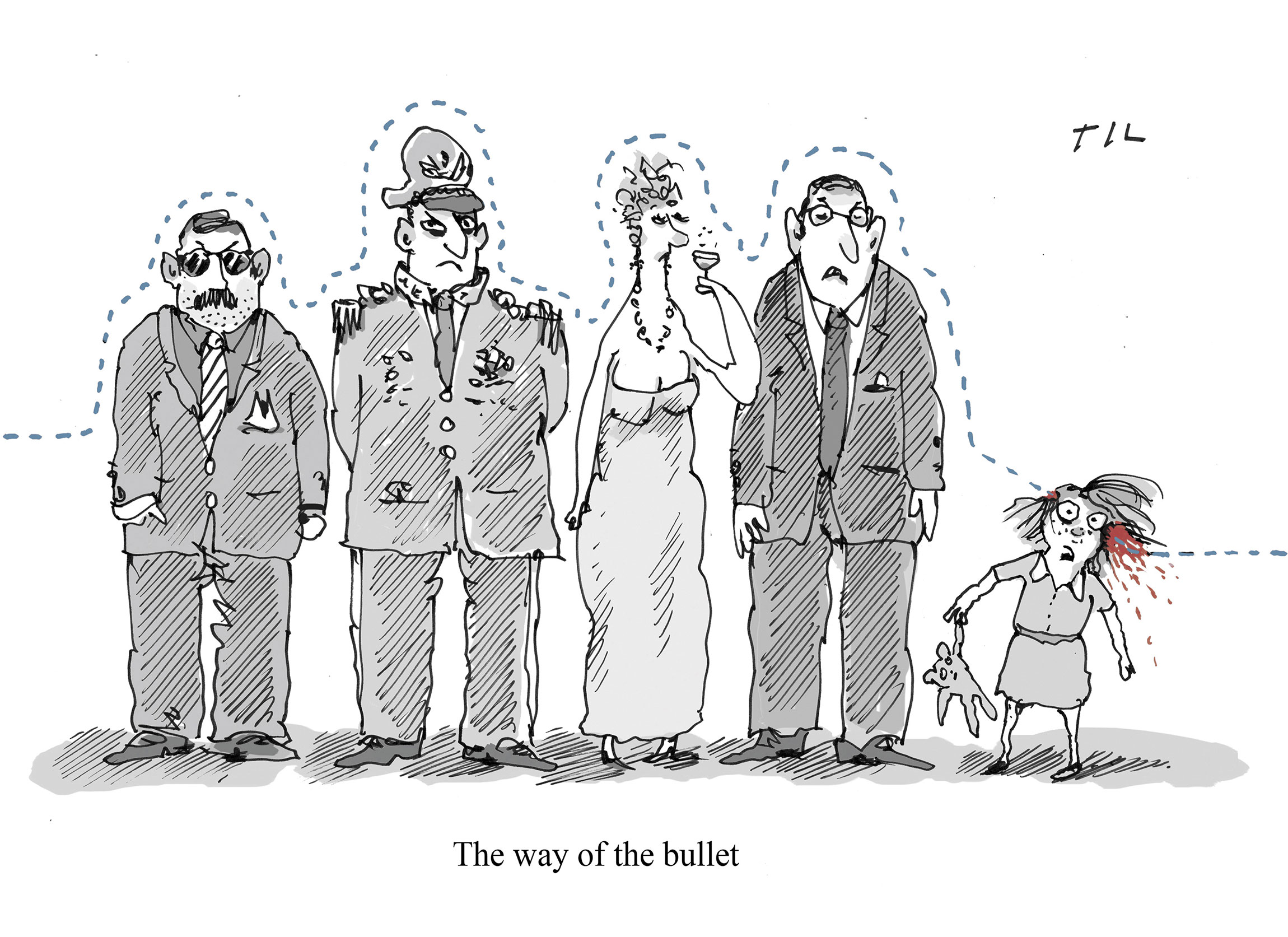

The good thing about the Green Pass is that it’s a constant reminder of what it’s like to not have a passport. We say: your freedom ends where mine begins. We could add: What does it actually mean to be free? We are talking about gesture-responsible-freedom à la Jacques Derrida (the same Derrida who was ashamed to be seen naked by his cat). And yet Green Passes mean different things to different people. For some, they allow ‘almost unfettered freedom to travel’, whereas others have to satisfy their desire for freedom by visiting the hairdresser.

On the Adriatic, about fifty kilometres north of Pescara and at the foot of the Gran Sasso, I had an opportunity to demonstrate the superpowers bestowed upon me by my expired Austrian passport. I was standing before a seemingly endless, four-lane, pale blue water slide. It was steep. Water was pouring down it. To get down, I had to sit in the water and let it carry me along. Faster and faster and faster and faster and faster and faster and faster. I plunged down blindly, water splashing in my face and eyes. I lost control of my body, was catapulted into the air and splashed into the depths, submerged and resurfaced. Such fun! My companion, who turned six two months ago, immediately wanted to do it again. Slide number eight!

We say: your freedom ends where mine begins. We could add: What does it actually mean to be free?

In the land where lemons grow, unlike in Vienna, he was young enough to enjoy such pleasures without a Green Pass. Only I had to show the QR code. The lemons were already hanging heavy on the trees. We climbed back up the hill. Waited in the four-lane queue for our turn. Via! That’s the code word. Not difficult to understand. But all the same. How would someone say it at Austria's Wolfgangsee? Uuuuand, owe middia? I honestly don’t know.

What I do know is that the Blue Wave, the Onda Blu, comes at eleven, three and four o’clock; it rolls along like a glittering, liquid crystal monster that lifts you up and renders you weightless. The ground under your feet disappears, then you’re set down again, surprisingly gently; but before you've rubbed your eyes, before you’ve really caught your breath, the next one comes, and then the next, or is it all the same one wave, as defined in the dictionary: 'the part of moving water that temporarily raises above the main surface of the water' or, somewhat less frequently, 'a wavy part of the hair'.

Without a word, the young superhero told me we can also communicate with gestures. After sliding down, he suddenly found he could swim. For the fourth time, we stood at the top looking down the sheer, blue waterfall. By now, we were recognised by the woman who decided when we could go. Her shout of via! was accompanied by a vigorous wave of the arm. Is there even a way to say via! in German? Maybe los? But how do you feel when you think los? Doesn’t the word contain a balloon that inflates when I think about it, pressing on my stomach, making me feel I will burst if I go now?

And doesn’t via catapult me to the Via Appia Antica, 312 BC, sending a laser beam through my body, making me long, elastic and invulnerable?