Jonathan Grix is the Editor-in-Chief of the leading International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics and External Examiner for Sport Politics at Loughborough University, United Kingdom.

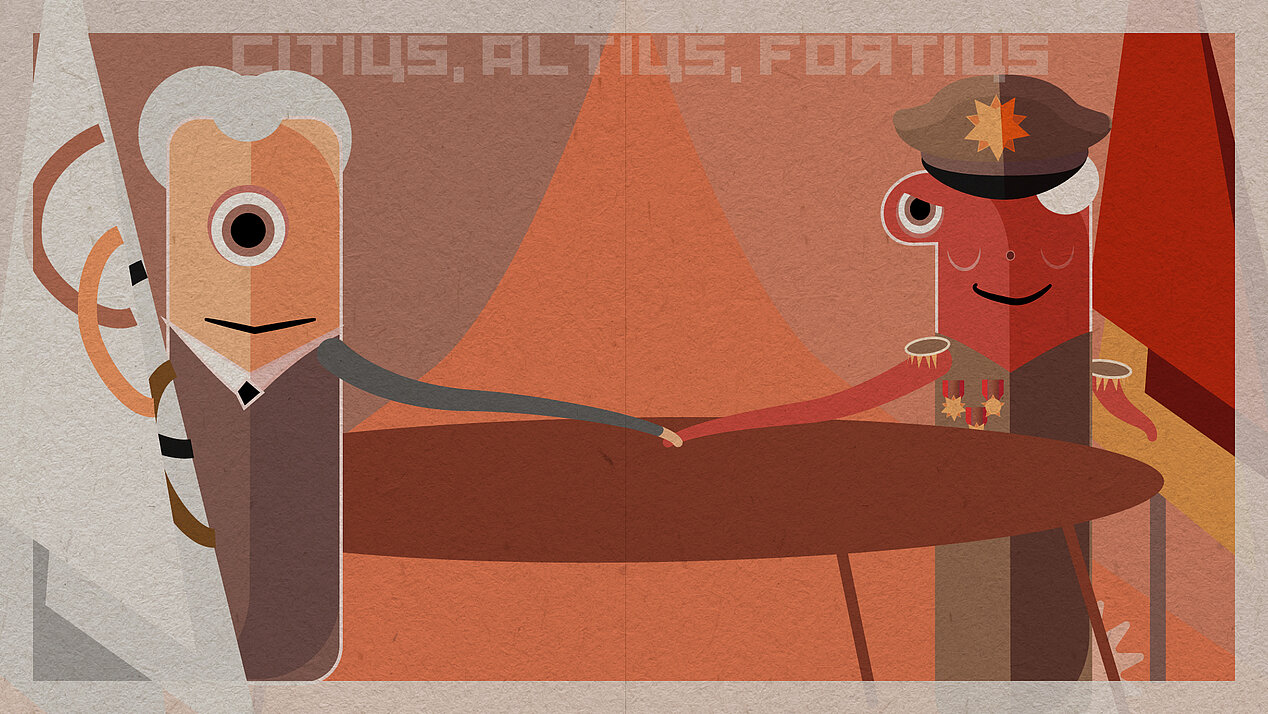

Twenty or thirty years ago an essay on sport and politics would have had to spend a few pages justifying why both concepts were being discussed together. Politicians, sports administrators and athletes themselves regularly lament how sport and politics are, and should be kept, separate. Writing today, however, against a backdrop of widespread doping in sport, corruption, misuse of public money, large-scale infrastructural projects developed in the name of sport and a spiralling ‘sporting arms race’ there is little space to waste on pondering the political in sport.

The challenge today is a different one: where to begin. Almost all aspects of sport are political – especially if we take the basic meaning of politics to be about the distribution of resources or, as the American political scientist and communication theorist Harold D. Laswell put it back in 1936, ‘who gets what, when and how?’ Sport has become a commodity, while the sport industry itself brings muchneeded revenue to state coffers; elite sport is used as a vehicle to enhance a state’s image on the international stage or as a chance for athletes to ‘hop’ from one nation to another and compete under a foreign flag, usually for financial gain.

Almost all aspects of sport are political.

Here I want to discuss some of the challenges facing global sport today and some of the historical precedents of those challenges. It begins by drawing on four important examples from German sport history that I believe are relevant to, and have shaped, the challenges facing global sport today.

A subsequent section then develops some of the key themes further, including politicians and the discourse of ‘legacies’ from sports mega-events (SMEs).

My conclusion is not that sport needs to be less political, but that we need to try to instrumentalise sport more for social good and less for financial gain.

Germany has played a much understated, yet central, role in the manipulation of sport for political purposes. The first example is what could be considered the start of ‘mega’ sports events – the so-called ‘Hitler Olympics’ of 1936. This is widely recognised as the first and most blatant use of sport for political purposes. The Nazis also introduced the torch relay.

The difference between the original political motives for instigating the relay and its use nowadays is enlightening. Whereas the Nazi regime used it to propagate their regime, it has now become an integral part of community engagement by the Olympic movement, in an attempt to whip up enthusiasm for the event rather than the hosts themselves.

The torch relay is now a target for protest groups seeking to draw attention to their cause, as was the case in the build-up to the Beijing Olympics and the highlighting of Chinese human rights abuse by Tibetan monks.

Another impact of the 1936 Games on today’s use of sport is its gigantism: the extravagant show put on by the Nazis – including 10,000 dancers performing a play and a 3,000-strong choir – has led to an exponential growth in bombastic showcasing during both the opening and closing ceremonies of the Olympics. Today, the host nation often attempts to improve its international image by being seen to be able to stage such a complex, multi-faceted and commercial event and the increase in costs associated with putting on a good show is a ‘sporting arms race’.

The torch relay is now a target for protest groups seeking to draw attention to their cause, as was the case in the build-up to the Beijing Olympics and the highlighting of Chinese human rights abuse by Tibetan monks.

The second German example is rooted in the tragic events of Munich in 1972, which saw the first political and calculated use of a major sporting event by terrorists and greatly influenced the manner in which subsequent sports mega-events are now ‘securitised’. After the meticulous planning and considerable effort Germany put into preparations for the 1972 Games, political terrorism intervened and 11 Israeli Olympic team members and one West German policeman were killed during a kidnap attempt by the Palestinian group Black September.

Had the Games finished a few days earlier, when a 16-year-old German had surprisingly won the Olympic high jump, despite being the third choice for her national team, Munich is likely to have gone down in sport history as Germany’s post-war re-integration.

What Munich does do is it reminds us of the risks involved in staging a major sport event; one of the key legacies of these Games is the ‘securitisation’ of sports mega-events, which reached its apogee at the recent London 2012 Games. In London, measures taken to prevent a Munich-type security disaster included surrounding the Olympic park with an 11-mile, £80 million, 5,000-volt electric fence – the UK even stationed anti-aircraft missiles on residential roofs close to the Olympic park. The ‘securitisation’ of such major events is now even more challenging since the ‘war on terror' post-9/11 and after the Paris terrorist attacks in 2016. This type of terrorism is likely to impact the way in which such events are run, consumed and enjoyed.

A third German example is that of East Germany, in which the manipulation of elite sport for political gains resulted in arguably the most successful sports system ever known. East Germany’s political instrumentalisation of sport for international recognition and legitimacy remains unparalleled. Their success in elite sport has had far-reaching and unintended consequences – the sports model de veloped and refined in the GDR continues to shape modern-day elite sports in advanced capitalist states.

There is a certain irony that East Germany collapsed, yet its sporting legacy continues to influence its erstwhile opponents. A majority of today’s best sporting nations have a system that is not too dissimilar to East Germany (many with widespread doping too).

The consequences of a focus on elite sport success and specific sport disciplines at the expense of support for some sports and grass-roots sport are obvious, yet there appears to be a consensus that elite sport success is ‘good’ for a state, despite a lack of evidence to suggest why this should be the case. The usual chestnut that ‘elite sport success’ or a ‘sports mega-event’ leads to higher rates of sport participation among the masses has not been borne out in research.

A fourth and final German legacy is the use of sports mega-events to change a nation’s image. It is fair to say that the 2006 FIFA World Cup (FWC) was an unmitigated success. As a country that had suffered from a poor image abroad for over 60 years, Germany set out to use the FWC to improve it on a global scale.

Of the key factors that made up the German strategy, the (unintended) creation of a feelgood factor around the four weeks of the tournament are of interest. Their fan-centred approach to the event led to the creation of unique fan-zones and fan-miles, where those people without tickets could watch the games live on very large screens. Over 20 million people joined in the party-like celebrations around the large viewing screens which were set up in the 12 host cities in Germany with no major public disorder reported.

The ‘Fan Fests’ served a number of purpo ses: first and foremost, they offered a streetparty atmosphere to fans and bystanders who did not have tickets or who did not want to watch the football in the stadium(s). These innovative ‘spaces’ also provided an arena within which fans and people, mostly women, who would not usually follow football, could enjoy a good party atmosphere. The well-functioning fan zones, excellent signage, trained personnel and first-class transport system provided an unintended by-product in the creation of a feelgood factor and carnival-like atmosphere among those outside the stadiums.

There appears to be a consensus that elite sport success is ‘good’ for a state, despite a lack of evidence to suggest why this should be the case. The usual chestnut that ‘elite sport success’ or a ‘sports mega-event’ leads to higher rates of sport participation among the masses has not been borne out in research.

In the current post-Paris climate it is unlikely that such a carnivalesque atmosphere will accompany a major sports event again because of terrorist threats, as security measures will, perhaps necessarily, work against the boundary-breaking communitas developed by experiencing sport together. Ironically, perhaps, one of sport’s most powerful side-effects – the ability to allow consumers to transcend cultural, religious and even class boundaries – is very likely to be nipped in the bud by the menace and threat of terrorism. The reason? For communitas to develop you need mass congregations, spontaneous gatherings of people before and after the sporting event, all factors that are likely to be discouraged, as the new terrorist threat seeks out innocent crowds of people.

Post-2006 it is clear that Germany’s attempt to alter its negative national image abroad was successful. I believe that this has influenced a number of so-called ‘emerging’ states to host major sporting events. However, most do not have the resources or know-how to undertake long-term planning prior to the event as Germany did; many do not have or are unconcerned about whether their population is behind the event; this then leads to them not having a clear strategy for the event, but rather a ‘hope’ that the event itself will simply lead to an improvement in their image.

The latter is all they share in common with Germany: a tarnished image in need of improving. Unfortunately, for such states hosting a sports mega-event might be the worst thing to do, as the media tend to focus hard on the reasons why a state has a poor reputation in the first place. Examples include Ukraine and the European football championships in 2012 (joint hosts with Poland), Qatar, South Africa and China. The jury is out on whether bidding for or hosting a sports mega-event has actually improved the image of the above states.

Arguably, Ukraine, Qatar and China came out worse in terms of how their image is perceived by citizens across the world; the extent to which this impacts on their ability to trade internationally and develop bilateral relations is, however, questionable. China has enjoyed unprecedented bilateral relations and agreements with the UK, despite the Beijing Olympics fore-fronting their abuse of human rights; Qatar continues to blossom, despite the global exposure of its human rights abuses, especially of foreign workers building the sporting infrastructure for the 2022 Football World Cup; Ukraine came under intense media scrutiny following its (joint) hosting of the 2012 European Football Championships.

There has been a recent trend of ‘emerging’ states bidding for and hosting sports megaevents, while, at the same time, many ‘advanced capitalist states’ have held referenda in which the public have rejected the idea of hosting.

The recent bid for the 2022 Winter Olympics is indicative of this trend and the problems that come with it. After voters in Munich, Stockholm, Krakow, and Graubünden, Switzerland, said no to the spiralling costs, hollow ‘legacy’ promises and security concerns, it was a race between Beijing – an area with very little snow – and Almaty, Kazakhstan. Both China and Kazakhstan do not fare well in lists on upholding human rights and on corruption – two factors that run counter to the fundamental Olympic ideals.

If the spiralling costs associated with hosting sports mega-events are left unchecked, it is conceivable that those states which care little about the views of their citizenry will be the only place in which such spectacles take place. Sochi is a case in point here – around US$55 billion was spent on the Winter Olympics, making it the most expensive Olympics ever (summer or winter). The usual post-event scenario of under-utilised, inflated sporting infrastructure is likely to be even more pronounced in Russia. Such a use of taxpayer’s money is no longer viable in a democratic state.

Yet politicians of all political hues love a sporting spectacle – generally in the hope of raising people’s spirits, improving their own popularity and in the hope of generating an economic return on their (that is the public’s) investment. They are also part of what could be termed a ‘coalition of beneficiaries’ – that is, those who seek to bring SMEs to their states and cities.

There has been a recent trend of ‘emerging’ states bidding for and hosting sports megaevents, while, at the same time, many ‘advanced capitalist states’ have held referenda in which the public have rejected the idea of hosting.

They are also responsible for the discourse that surrounds such sporting spectacles, often promoting the many ‘benefits’ or ‘legacies’ that will befall society should they choose to host. Research on the prospects of such ‘legacies’, however, suggests that the coalition of beneficiaries are likely to benefit from large-scale sports events, whereas the general population is not. And here we return to Harold D. Lasswell – if people are to be persuaded to invest in elite sport programmes or the hosting of sports megaevents, then the case for post-event legacies needs to evidenced. At present, would-be legacies are generally hoped-for rather than specifically and strategically aimed for. The perennial sports mega-event question is not ‘what happened to the legacy’, but rather ‘why do states not learn from previous events’? The answer to this is that the coalition of beneficiaries does learn – usually firms involved in construction, event stakeholders, politicians, hospitality trade and so on; it is in their interests to host.

If there is any doubt left remaining, a final example of sport’s political nature will suffice to show how closely politics and sport are linked. If ever anybody needs convincing of such a link, they can do no worse than consider the role of the key international sporting organisations. We have arrived at the absurd situation whereby undemocratic international sporting organisations such as FIFA and the IOC are able to demand changes to laws in sovereign, democratic states to be able to host their showcase events. Thus, Brazil’s economic governance of state capitalism had to tweak many laws to do with employment and procurement to meet the requirements of both FIFA and the IOC.

The net result, one could surmise, is that in order to receive such prestigious events, states need to become just a little more neoliberal.

The Olympics has developed into the most commercial sporting event on the planet and is probably about as far from Pierre de Coubertin’s revival of the modern Games in 1896 as you can get. Sponsorship and commercial rights – including the Olympic brand itself – have become far more important than the actual sport and to safeguard top Olympic sponsors and allow them generous tax breaks, hosting state need to adjust their laws.

The latter is indicative of how far we have come – sport is very big business; athletes are prepared to go to any lengths to succeed in this ‘win at all costs’ culture, so we should not be surprised at revelations of widespread corruption and the use of performance enhancement drugs. While it would be ludicrous to advocate sport without politics, there is reason to believe that we have reached a tipping point at which more effort is needed to turn the tide so that politics no longer dominates sport, but rather uses it to achieve common goods.

Jonathan Grix is the Editor-in-Chief of the leading International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics and External Examiner for Sport Politics at Loughborough University, United Kingdom.

Culture has a strategic role to play in the process of European unification. What about cultural relations within Europe? How can cultural policy contribute to a European identity? In the Culture Report Progress Europe, international authors seek answers to these questions. Since 2021, the Culture Report is published exclusively online.