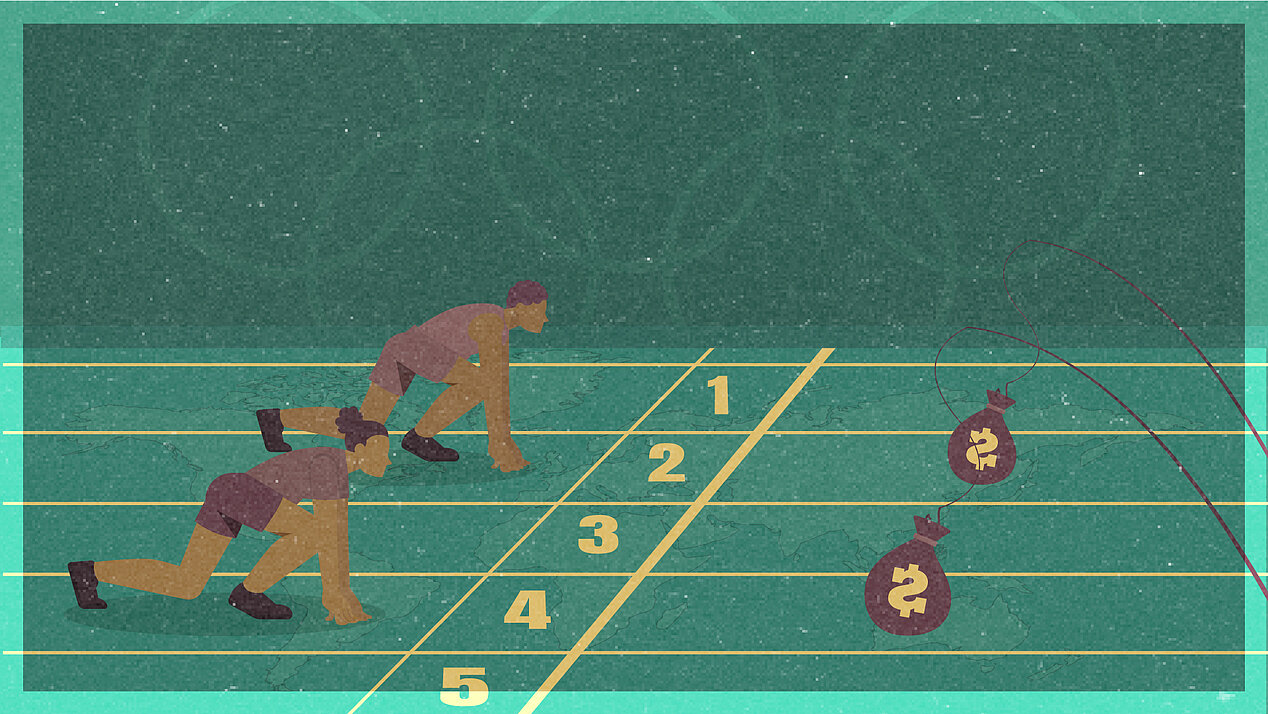

So turning sporting success into international prestige must begin by obeying the rules. Whether that is actually the case on the field of play is now a lot easier for the viewer to determine thanks to today’s sophisticated technology. But whether everything is done properly off the field of play, that is to say during preparation and training, can only be determined to a limited extent because of the lack of an effective global monitoring system.

The question international sports fans have to ask themselves is whether they trust a particular athlete, country and sports system. This question of confidence when it comes to sporting success has been highlighted in certain remarks about Jamaican sprinter Usain Bolt. In the survey mentioned above, Bolt was the international athlete who was most often mentioned for evoking positive memories. But he was also came second when it came to evoking negative memories because many people found it hard to believe that he could turn in such performances and still be ‘clean’.

The reason so many cities in Western democracies are increasingly reluctant to host the Olympics is not because the people [...] have lost interest in sport per se [...], but because they are evidently not interested in the kind of sport that the IOC stands for.

However, in sport, especially Olympic sport, being ‘clean’ is generally a necessary, but not always sufficient, prerequisite for success to be recognised. When it comes to abiding by the rules, many people in many countries (precise data on this issue is lacking) also expect adherence to the informal principles of fair play. The word ‘Olympic’ stands for the promise of respectful, peaceful, ‘humane’ competition, in which success should not be achieved at the expense of all other values. At least this is what it once claimed to stand for (similar to the Fairtrade label on food).

Of course, these expectations do not only extend to the behaviour of individual sportsmen and women in specific competitive situations, but also to the more abstract competition that takes place amongst nations, and not least to the way countries’ sports systems and officials deal with their own athletes. As a result, the sporting success that emanates from the hosting of major sports events by countries with dubious regimes is not necessarily met with blanket international enthusiasm, especially if it is perceived that certain standards have not been maintained.

Conversely, democratic states that also push the boundaries of these standards in an attempt to maximise success and improve their self-image also run the risk of alienating their own sporting population. The reason so many cities in Western democracies are increasingly reluctant to host the Olympics is not because the people of Hamburg, Oslo or Boston have lost interest in sport per se – the people of these cities are actually significantly more active than ever before – but because they are evidently not interested in the kind of sport that the IOC stands for.

As we know, the GDR was particularly involved in developing a state sports system that had a major impact on the nature and direction of Olympic sport, all in an effort to gain international recognition and demonstrate its superiority over the West. This system included well thought-out and highly organised doping practices, along with legal measures to identify and train talented children and young athletes. State funding was funnelled into those sports that offered the best chances of winning medals. The GDR and the Cold War may be long gone, but many of their strategies have been adopted by other countries around the world – not just China and North Korea, but also many ‘Western’ nations.

Britain is now viewed as a key example in this respect. After many years of poor performances, it is once again an Olympic superpower, thanks to a ‘no compromise’ strategy that involves pouring money into sports that offer a good chance of victory, while totally withdrawing support from other less successful sports. According to the German Minister of the Interior, Germany will also undertake a programme of far-reaching reforms after the Rio Olympics, and it is likely to focus more strongly on sports that offer the best chance of winning medals.

Leaving the moral aspects aside for a moment, let us look at the actual effectiveness of this kind of sports policy strategy. Does success in Olympic sports actually have the same positive impact on people’s perceptions of a country, as is the case with football? The initial answer is: it depends. Winter sports naturally involve a much smaller circle of nations who can participate in competitions. But the different sporting disciplines at the summer Olympic games are also followed with varying degrees of interest around the world. Surveys suggest that many Germans still view winning medals in athletics and swimming as far more important than success in other sports – and these two disciplines are generally the ones that attract the largest viewing figures.

Globally, the 100-metre sprint (especially the men’s) is considered to be much more prestigious than, say, the light welterweight boxing competition.

Britain is now viewed as a key example in this respect. After many years of poor performances, it is once again an Olympic superpower, thanks to a 'no compromise' strategy […].

Then again, you wonder whether Germany’s strong medal tally in canoeing has much influence on the global perception of the country, particularly as interest in this sport mainly comes from Eastern Europe and other nations that pursue a wide range of sports (though not the USA). In short, apart from a few globally popular competitions, international audiences are very much focused on specific sports and can vary significantly in size. This means that the potential for attracting international attention and improving a country’s image through sporting success also varies widely from sport to sport.

Germany’s sports policy is generally not interested in such subtle distinctions, as the government does not support individual sports, but leaves the distribution of funding to the German Olympic Sports Confederation (DSOB). Success is generally measured in terms of the overall medal haul and the country’s position on the medal table. Ignoring the fact that this is not considered an official ranking by the IOC – Rule 57 of the Olympic Charter prohibits the drawing up of any global ranking by country in order to avoid international disputes and sporting arms races – the medal table still provides an abstract form of ranking that offers other, more limited, benefits in terms of prestige.

As our Dutch colleagues have remarked: medal tables don’t tell any stories! That is left to the individual competitions, and to the competitors and teams involved. Chinese athletes continue to be unknown, despite the fact that they won 100 medals in front of their home crowd (including 51 gold medals), with China topping the medal table. However, one story that many people remember is one of failure, namely that of the hurdler Liu Xiang, who as defending champion was forced to drop out of the competition at the last minute due to injury.

It is ‘Olympic moments’ like these that stir up our emotions and remain in our memories for years to come – no matter where we live. They cannot be planned, whatever a country’s sports policy, nor can they be identified from a scan through the medal table.

People were asked to think back to the last Olympics and say whether individual sportsmen and women, or even countries as a whole, evoked negative memories. China, the most successful nation in 2008, was the country most often cited by a long, long way, not only because of suspicions of doping, but also because respondents felt that China’s young sportsmen and women were being instrumentalised and drilled too hard.

The same applies to the other promises that are made to justify funding and support for elite sport. For example, there is no empirical evidence to support the idea that sporting success leads to a lasting sense of patriotism or national pride.

Football is somewhat less vulnerable to outside influence by the state due to its commercial success and can therefore project a more realistic image of human endeavour (‘first food, then morals’), whereas Olympic sport (or many of the sports represented at the Olympics at least) relies much more heavily on public funding and therefore tries much harder to prove its legitimacy through its apparent or actual social achievements.

It also cannot be proved that success in elite sport leads to more people taking up sport. If sport is a public affair (and if it is funded by the state, then it definitely is), then it is important to ask what sport we really want. What role should the chances of success really play and what emphasis should be placed on other considerations? Of course foreign policy issues should be included in any such debate. And we can certainly discount the idea that ‘the more we win, the more people will love us’.

Culture has a strategic role to play in the process of European unification. What about cultural relations within Europe? How can cultural policy contribute to a European identity? In the Culture Report Progress Europe, international authors seek answers to these questions. Since 2021, the Culture Report is published exclusively online.