Difficult Dealings with “Disinformation”

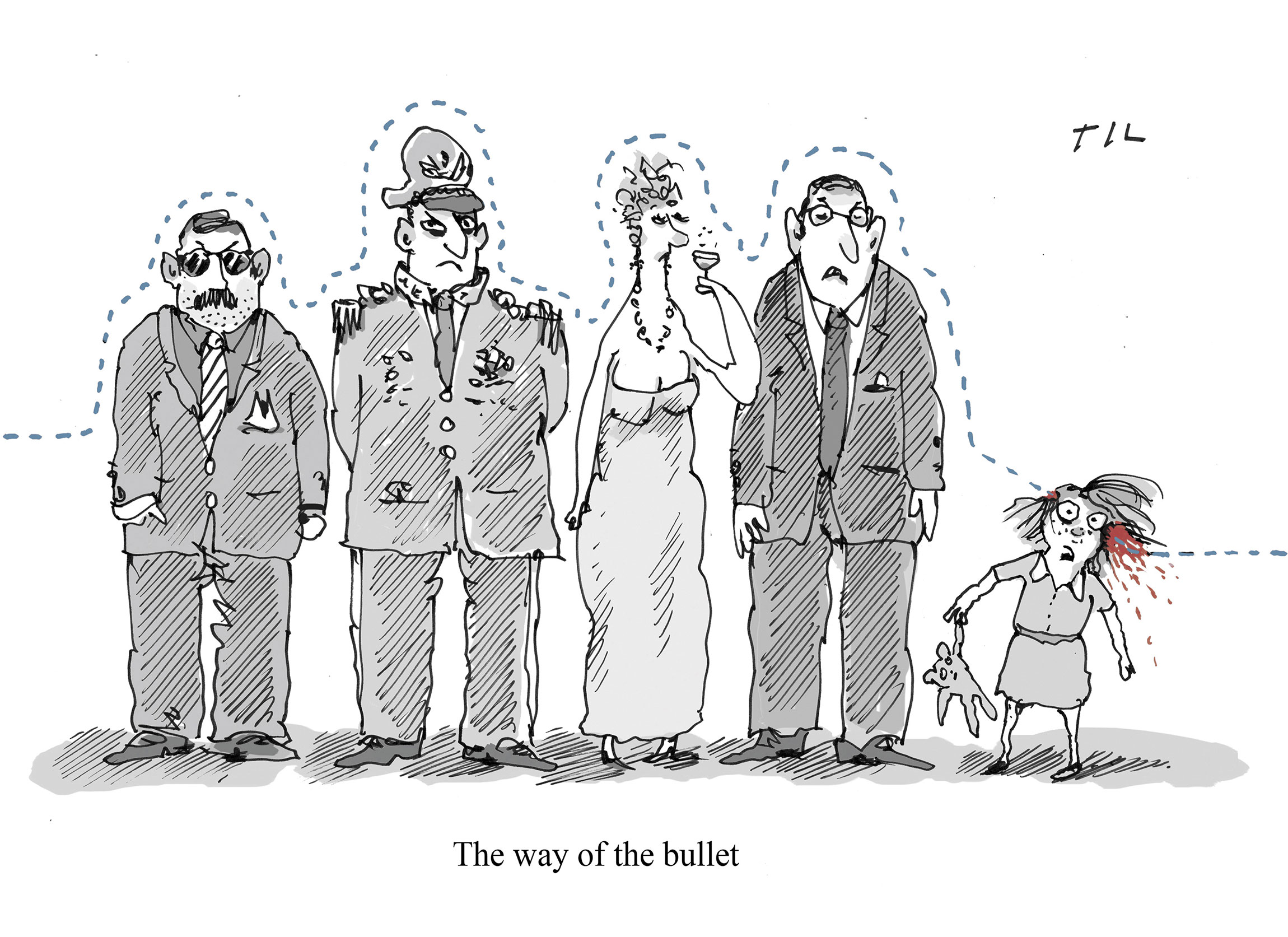

In October 2022, the Turkish government adopted the so-called ‘Disinformation Act’. Whoever spreads “fake news” on social media faces up to three years in prison. This applies not only for journalists, but also for private social media users. What is legally meant by the terms “fake news” and “disinformation”?

Di Fabio: “Disinformation” or “fake news” are vague terms which must be handled with care from a legal perspective. Although a statement of fact which has been demonstrated to be untrue does not automatically come under the protection of freedom of expression, often – apart from impudent and evident lies – imprecise wording is used, controversial data, lop-sided correlations or a selective presentation of facts and their weighting which, according to the case law of the German Federal Constitutional Court, must remain permissible within the scope of protection of freedom of expression to ensure that the boundaries are not drawn too tightly.

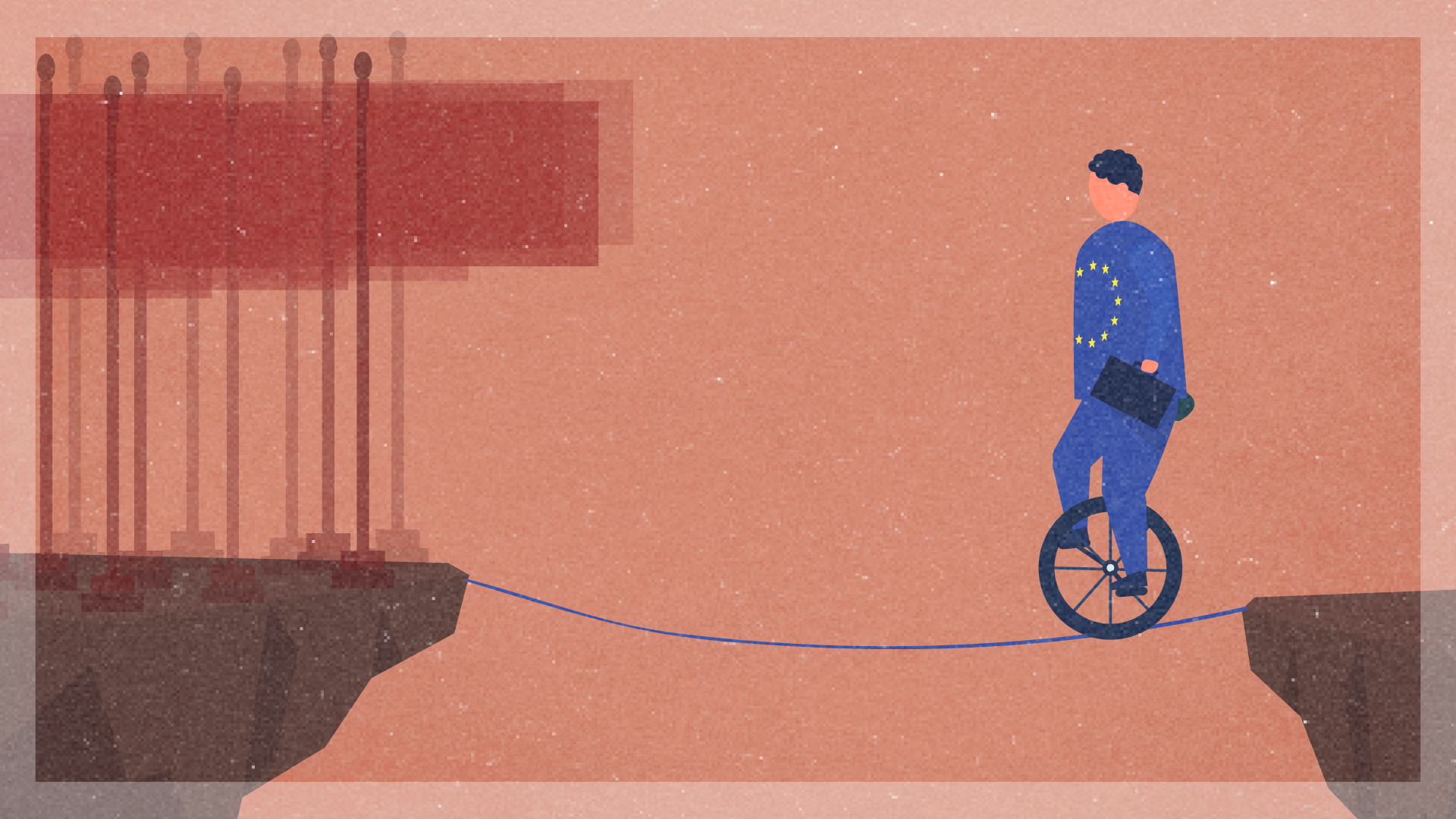

The term ‘disinformation’ has been used much more often, especially since Trumpism, and it is regarded as a problem – in Germany as well. Even the German Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution is considering whether intentional disinformation, which often comes from abroad and systematically damages democracy’s reputation, should be placed under observation. The problem is that then autocracies will come and say: we know all about this particular phenomenon and that is why we forbid factual claims which, from our point of view, are false and why certain evaluations are punishable by law. It is important that we continue to regard opinions in a friendly manner so that we are also credible, for example in our relations with Turkey.