If you are, as I am, a spectateur engagé, you can also contribute to that political enterprise EU simply by bringing home the historical truth. I would argue that for three generations after 1945, the most important single motor of European integration was individual, personal memories of war, occupation, Holocaust and Gulag, of dictatorships – fascist or communist –, and extremes of nationalism, discrimination and poverty. Now, for the first time, we have a whole generation of Europeans most of whom – not all, but most – have grown up since 1989 with none of those traumatic and formative experiences.

They have known only a Europe largely whole and mainly free. Almost inevitably, they incline to take it for granted; for there is a universal human tendency to perceive what you grow up with and see around you as in some sense normal, even natural. Czeslaw Milosz describes this phenomenon memorably in his book ‘The Captive Mind’, comparing us to Charlie Chaplin in the film ‘The Gold Rush’, bustling around cheerfully in a wooden shack hanging perilously over the edge of a cliff.

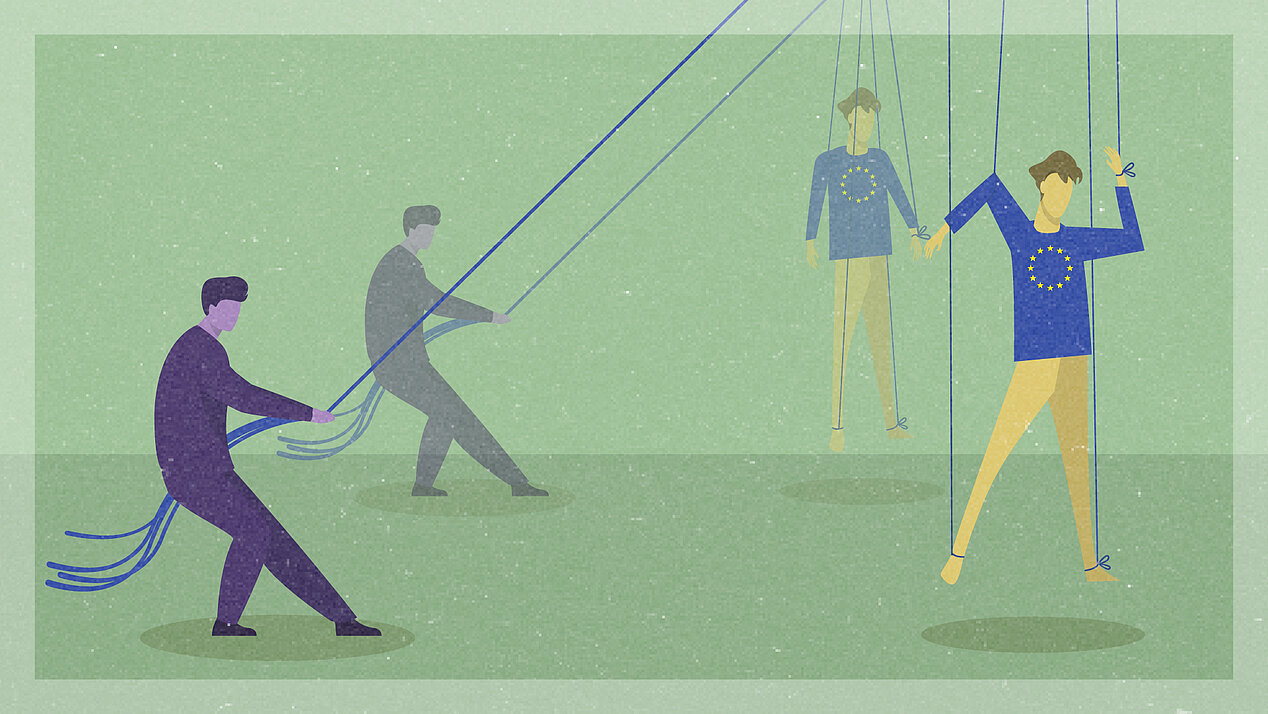

For three generations after 1945, The most important single motor of European integration was individual, personal memories of war, occupation, Holocaust and Gulag, […].

I hope we're not that far gone but we do need somehow to convey to this generation that what they today take to be normal is in fact, in historical perspective, profoundly abnormal – exceptional, extraordinary. In a speech, Pope Francis mentioned Elie Wiesel's call for a ‘memory transfusion’ to younger Europeans. Exactly so.

Of course nothing can compare with the impact of direct, personal experience. Yet one purpose of studying history is precisely to learn from other people's experiences without having to go through them yourself. Among the encouraging signs in recent months is a new mobilisation among this post-1989 generation of Europeans, who are showing that their pulse does beat faster for Europe.

Another, more general lesson from history is that what were originally just means to an end can come with time to be treated as ends in themselves. (Anyone who has ever tried to abolish a committee in a university, or any other institution, will know what I mean.)

In his opening speech to the original Congress of Europe in The Hague in May 1948, the man who would subsequently be the first recipient of this prize, Count Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi, said: ‘Let us never forget, my friends, that European Union is a means and no end’. This from a high priest of European unification, at a time when European Union was still only a dream.

His warning is very relevant today. All the European institutions we have created are means to higher ends, not ends in themselves. At every turn, we should ask ‘is this institution or instrument still fit for purpose, the best available for that purpose?’

It is no use just parroting ‘more Europe, more Europe’. The right answer will often be that we need more of this but less of that. Only an organisation capable of redistributing power both downward and upward, as changing needs require, will be seen by its citizens as alive and responsive.

And then there is the dichotomy most characteristic of European history: that of unity and diversity. In Aachen, we inevitably think of the Holy Roman Empire, Europe's longest lasting empire. The historian Peter Wilson argues that one reason the Holy Roman Empire did survive so long is that its overarching structures were seen as securing and protecting the enormous diversity of political, ecclesiastical and legal communities under its aegis, not threatening them with excessive centralisation and homogenisation.

Its legitimacy and longevity derived from its ability to live with this complexity, and hence with a level of chronic discord: ‘although outwardly stressing unity and harmony, the Empire in fact functioned by accepting disagreement and disgruntlement as permanent elements of its internal politics’. I think there's a lesson there for the European Union.

Our contemporary European diversity is not just of states and histories, but also of cultures and the languages in which they are embedded. These profound differences of culture, language and philosophical traditions also cut deep into the way we think about the state, law and politics, and therefore about the political order to be constructed between our states and peoples.

Europe will be stronger if it can accommodate all these kinds of diversity. Medical science identifies two contrasting problems with joints: hypermobility, meaning the joint is too loose, and hypomobility, meaning the joint is stuck tight.

Europe will be weakened if its structures become too loose, but also if they are too rigid. Like an Olympic athlete, Europe needs to be both strong and flexible: strong because it is flexible, flexible because it is strong.

All the European institutions we have created are means to higher ends, not ends in themselves.

By now you will have realised that I have been leading you in a kind of rapid motion Blue Danube waltz through a series of dichotomies: the individual and the collective, historical time and political time, the intellectual and the politician, means and ends, national and European, realism and idealism, and, last but not least, complexity and simplicity.

For at the end of the day, what we want is really quite simple: it is for people in Europe to enjoy freedom, peace, dignity, the rule of law, adequate prosperity and social security. It's how we achieve those simple goals that are so necessarily complicated.

Let me in conclusion say a few words to Germany and the Germans.When I first came to Germany, in the early 1970s, the shadows of the Second World War and Nazi dictatorship were still omnipresent. (My first research project was on Berlin in the Third Reich.) The country was still painfully divided, and I experienced at first hand that second German dictatorship which the whole world now knows by one short ugly word: Stasi.

Then came the year of wonders 1989, and Germany received, quite unexpectedly, what the historian Fritz Stern famously called its ‘second chance’. For more than a quarter century now I have watched with growing admiration how well united Germany has used this second chance.

I personally find it extremely moving that refugees from all over the world now look towards Germany, as if it were the Promised Land. It is rather wonderful that Germany now stands like an island of stability, moderation and liberality in the midst of an ocean of nationalist populism. Every time I contemplate this historical turning from darkness to light, it fills me with real delight.

Wise leadership in Europe requires a highly developed ability to see Europe also through other Europeans’ eyes.

But – there's always a ‘but’ – the second chance, or to be more precise the second half of the second chance, is still before you – the all-European half. With a new, decidedly pro-European French president, Germany and France once again have the chance to go ahead together, as so often before in the history of European integration. This second half of the second chance will, however, not be easy. Germany still faces the old, familiar problem of its ‘critical size’ – too small and yet too large; too large and yet too small.

Wise leadership in Europe requires a highly developed ability to see Europe also through other Europeans’ eyes – it needs Einfühlungsvermögen. It also requires steadiness, confidence and courage.

President Frank-Walter Steinmeier made ‘courage’ the central keyword of his inaugural address. That must include the ‘courage to speak the truth’ of which president Emmanuel Macron has spoken so powerfully. But it also includes the courage to compromise. The courage to live with uncertainty, incompleteness, even ambiguity – as in the Holy Roman Empire.

In short: life is not a Gesamtkonzept. And that's especially true of the political life of Europe. In a book on the history of Berlin published more than 100 years ago, Karl Scheffler wrote that Berlin is ‘fated always to be becoming and never to be’.

One could say something similar about Europe. We will never arrive at that sublime moment when we can cry: ‘there it is, the finished Europe! La belle finalité européenne – Verweile doch, Du bist so schön!’

No, Europe too is fated always to be becoming and never to be. But that need not necessarily be a curse, it can even be a blessing. When you're somewhat older you realise that the years of becoming are often the best years of one's life. Thus our ancient Europe has a chance to remain forever young. Let us then shape it together – Europe's never ending becoming.

Culture has a strategic role to play in the process of European unification. What about cultural relations within Europe? How can cultural policy contribute to a European identity? In the Culture Report Progress Europe, international authors seek answers to these questions. Since 2021, the Culture Report is published exclusively online.