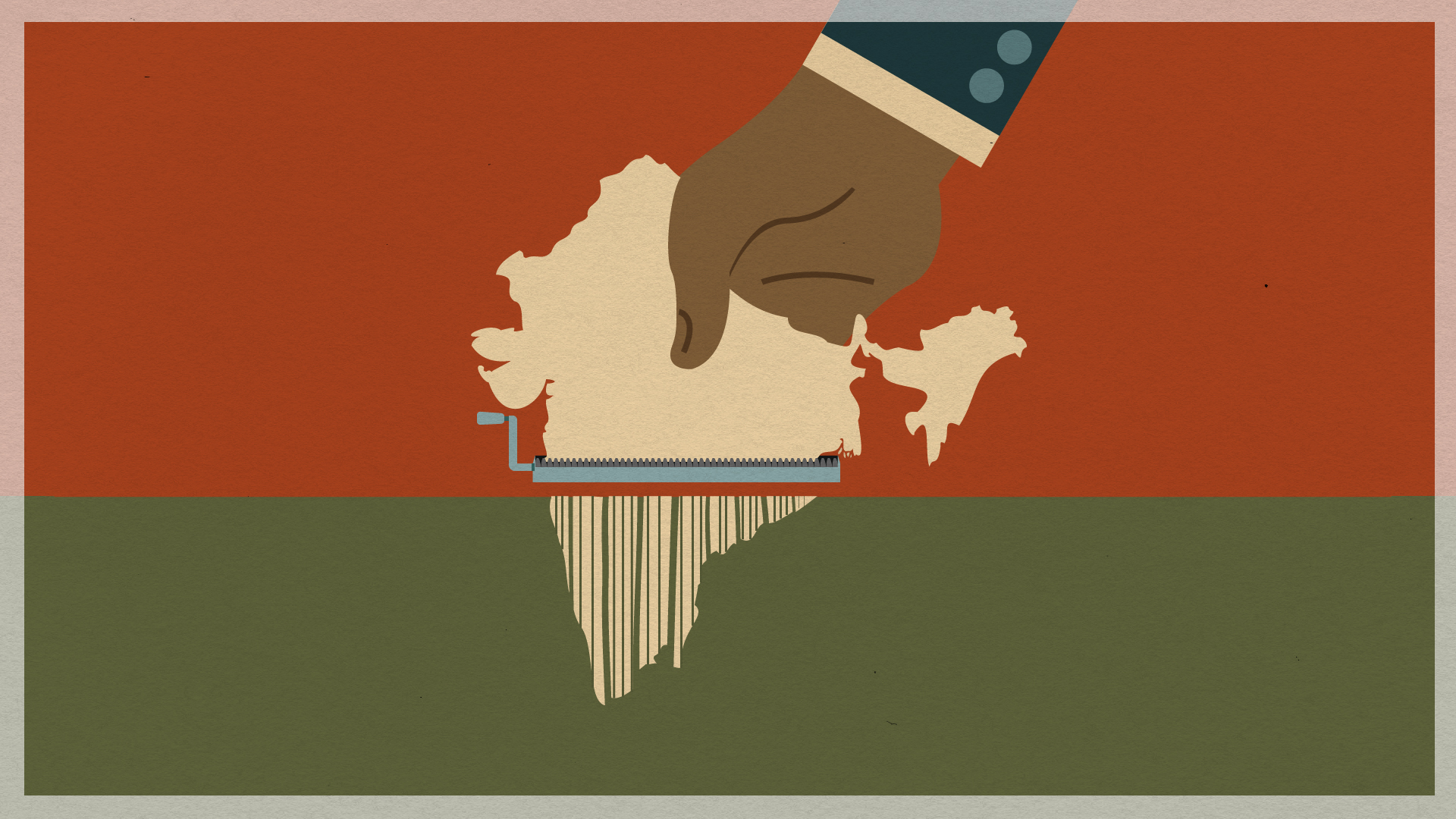

The developing world has a long history of suffering from colonialism and imperialism. Western colonial powers overturned traditional political structures, suppressed local cultural divisions, and remade societies for their own purposes. These actions were justified — when they were justified — as being necessary to ‘civilise’ the rest of the world according to Western norms. This was why elites were sent to be trained in Western ideas in British and French universities, or why the United States justified its own colonial endeavours on getting non-Western societies ‘ready’ for democracy.

In practice, colonial powers did little to improve their colonies. When they were granted independence after the Second World War, postcolonial states were left with little in the way of governing institutions, which often led to more conflict. It has taken decades for many of these colonies to make up the shortfall; some former colonies have yet to do so.

Thus, one can understand why the developing world looks sceptically at any attempt to impose a universal culture. They’ve seen how this language was used before to justify a programme of imperialism. Western leaders may claim over and over again that this time will be different — sometimes completely sincerely — but developing countries know where these words lead.

When they [the colonies] were granted independence, postcolonial states were left with little in the way of governing institutions, which often led to more conflict.

But the West and the rest are not just approaching the world with different experiences. They also face different futures as we move into a resource-constrained 21st century.

It is clear that our overuse of resources is having a dire effect on society, from climate change and extreme weather to soil pollution, increasingly scarce commodities and overheated cities. The world will need to move towards a more sustainable economic model that does not rely on rampant consumptiondriven growth at all costs and instead places resource management at the heart of economic planning.

They [the West and the rest] also face different futures as we move into a resource-constrained 21st century.

But the developed and developing world will see this challenge differently. Western nations are wealthy, having benefited from many decades of economic growth. They have largely met the universal basic needs and provided satisfactory social services to their populations, which are relatively small and not growing in size (if not declining). Their growth happened in a time of more plentiful resources, allowing them to overuse common and public resources without suffering the consequences.

![[Translate to english:] Ein Europa, das sich darauf konzentriert, die eigenen Institutionen zu stärken, wird weit mehr zu weltweitem Wohlstand beitragen als ein Europa, das andere belehrt, Foto: Zoonar / Christian Decout via picture alliance [Translate to english:] Die Flaggen der Mitgliedsstaaten der EU vor dem Europäischen Parlament in Straßburg.](/fileadmin/Content/images/mediathek/blog/Forum_Blog/ifa-forum_chandran-nair_flags_foto-christian-decout-zoonar-picturealliance263117662.jpg)