Between heresy and non-belief

The idea that underlies a united Europe got corrupted, half-forgotten, and it is only in a moment of danger that we are compelled to return to this essential dimension of Europe, to its hidden potential. Trump and Putin both supported Brexit; they supported Eurosceptics on every corner, from Poland to Italy. What is it that bothers them about Europe, given that we all know the misery of the EU, which fails again and again at every test: from its inability to enact a consistent politics about immigrants to its miserable reaction to Trump’s tariff war? It is obviously not this actual existing Europe, but the idea of a Europe that flares up against all the odds in in moments of danger. The problem for Europe is how to remain faithful to its emancipatory legacy, which is threatened by the conservative populist onslaught?

The only way to really defeat populism is to submit the liberal establishment itself, its actual politics, to a ruthless critique which can sometimes also take an unexpected turn.

In his Notes Towards a Definition of Culture, the great conservative T.S. Eliot remarked that there are moments when the only choice is the one between heresy and non-belief, when the only way to keep a religion alive is to perform a sectarian split from its main corpse. This is what has to be done today: the only way to really defeat populists and to redeem what is worth saving in liberal democracy is to perform a sectarian split from liberal democracy’s main corpse. Sometimes, the only way to resolve a conflict is not to search for a compromise but to radicalise one’s position.

Back to the letter of the 30 liberal luminaries: what they refuse to admit is that the Europe whose disappearance they deplore is already irretrievably lost. The threat does not come from populism: populism is merely a reaction to the failure of Europe’s liberal establishment to remain faithful to Europe’s emancipatory potential, offering a false way out of ordinary people’s troubles. So the only way to really defeat populism is to submit the liberal establishment itself, its actual politics, to a ruthless critique which can sometimes also take an unexpected turn.

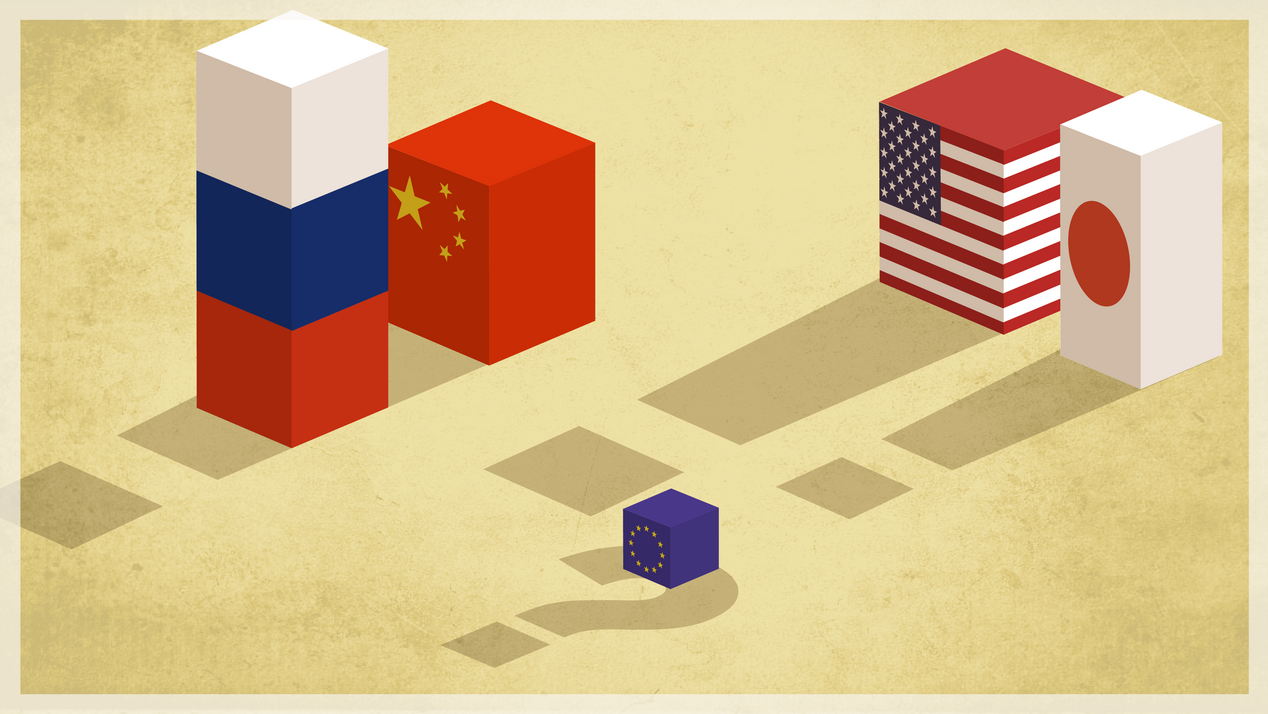

For example: does Europe need its own army? Yes, it needs it more than ever. But why, when we all know that the most sickening excuse for joining the arms race is that, when our prospective enemies are arming themselves, the only way to deter war and protect peace is for us to also get ready for war? Already, for a decade or so, the arms race between three superpowers (US, Russia and China) has been exploding at a frantic pace.

The entire Arctic area is becoming militarised; billions are being invested in military supercomputers and biogenetics. Chinese military journals openly debate the need for China to engage in real war (while the Russian military has recently been tested and still is by conflicts in Ukraine, Syria, etc., the Americans in Iraq, the Chinese army has avoided a real fight for decades).

![[Translate to english:] Ausstellungseröffnung in Novi Sad, 2022. Performance vor Nevin Aladağs Wandteppichen, Foto: alpha video, © ifa [Translate to english:] Wandteppiche von Nevin Aladağ hängen an einer weißen Wand. Auf dem Boden davor liegt ein Mann, nur mit einer schwarzen Hose bekleidet.](/fileadmin/Content/images/mediathek/blog/Forum_Blog/ifa-forum_evrovizion_novi-sad2022_eroeffnung.png)