The Commission should say, therefore, how it intends to use the EU budget to ensure the necessary comprehensive approach to the cultural aspects of Agenda 2030. It should also say how it will work with EU governments. Will there be synergy between the EU budget and the European Development Fund, financed by EU Member States outside the EU budget?

This is an area – culture as a dimension of sustainable development – where Europe, if it wants to, could lead the world. The newly elected European Parliament (2019–2024) should see to it that a policy paper is produced, and that its main conclusions will be agreed between the Council, the Commission, and the Parliament.

European governments, too, could show a little more spine. In January 2016 Turkish academics known as Academics for Peace published a petition entitled “We will not be a party to this crime”, which condemned anti-terror policies in the south-eastern part of Turkey and urged the authorities to resume peace negotiations. Hundreds of signatories were subsequently charged under anti-terrorism laws. In the wake of the coup attempt, later that year, more than 6,000 academics have been dismissed from their posts; hundreds have been detained or arrested. In both cases the EU’s feeble response failed to impress Ankara.

The European Union’s feeble response failed to impress Ankara.

The increasing virulent attacks on academic freedom deserve a more vigorous European response. EU ministers of education should recognise the importance of academic freedom as a cornerstone of education. The Foreign Affairs Council should include academic freedom in the EU’s international dialogues on human rights, as the European Parliament proposed. The European Commission should also play its part. A few EU countries operate small schemes to provide sanctuary and assistance to scholars at risk. There is little coordination, and the schemes lack visibility. An EU-wide scheme would not be difficult to conceive.

Academic freedom is a dimension of the wider right of everyone to take part in cultural life. This fundamental right is under threat both from authoritarian governments and from violent fundamentalists. When Egypt incarcerated the poet Galal El Behairy for writing a song critical of government policies, when jihadist groups banned music in Northern Mali, when China arrested five Hong Kong booksellers, or when Russia silenced the Ukrainian filmmaker Olav Sentsovby arresting him on Interterrorism charges, to cite just some cases out of many, they were striking at cultural freedom.

Freedom of expression is perhaps the most basic human right. It is the right on which all other rights depend. Freedom of expression is what dictators trample when they silence the voices of journalists, writers, singers, filmmakers and other artists. It is telling that artists who reach large numbers of people, such as musicians and filmmakers, are among the most vulnerable. As spaces for cultural freedom are shrinking in many parts of the world, cultural freedom needs champions. Could there be a more suitable priority for European cultural diplomacy?

Cultural freedom is firmly anchored in international law. It is protected under Article27 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 15(3) of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, and Article 19(2) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. It is closely related to other rights, such as the right to education (Articles13 and 14, ICESCR), through which individuals and communities pass on their values, religion, customs, language and other cultural references.

As spaces for cultural freedom are shrinking in many parts of the world, cultural freedom needs champions.

European initiatives could be instrumental in two respects: the EU could use political pressure to promote the respect of cultural freedom, and it could engage in partnerships to support public and private cultural action. At the moment, the EU does a little bit of both, its policies mostly driven by low-level bureaucratic entrepreneurship. In 2014 EU ministers adopted guidelines on freedom of expression online and offline, but application by national diplomats has been haphazard.

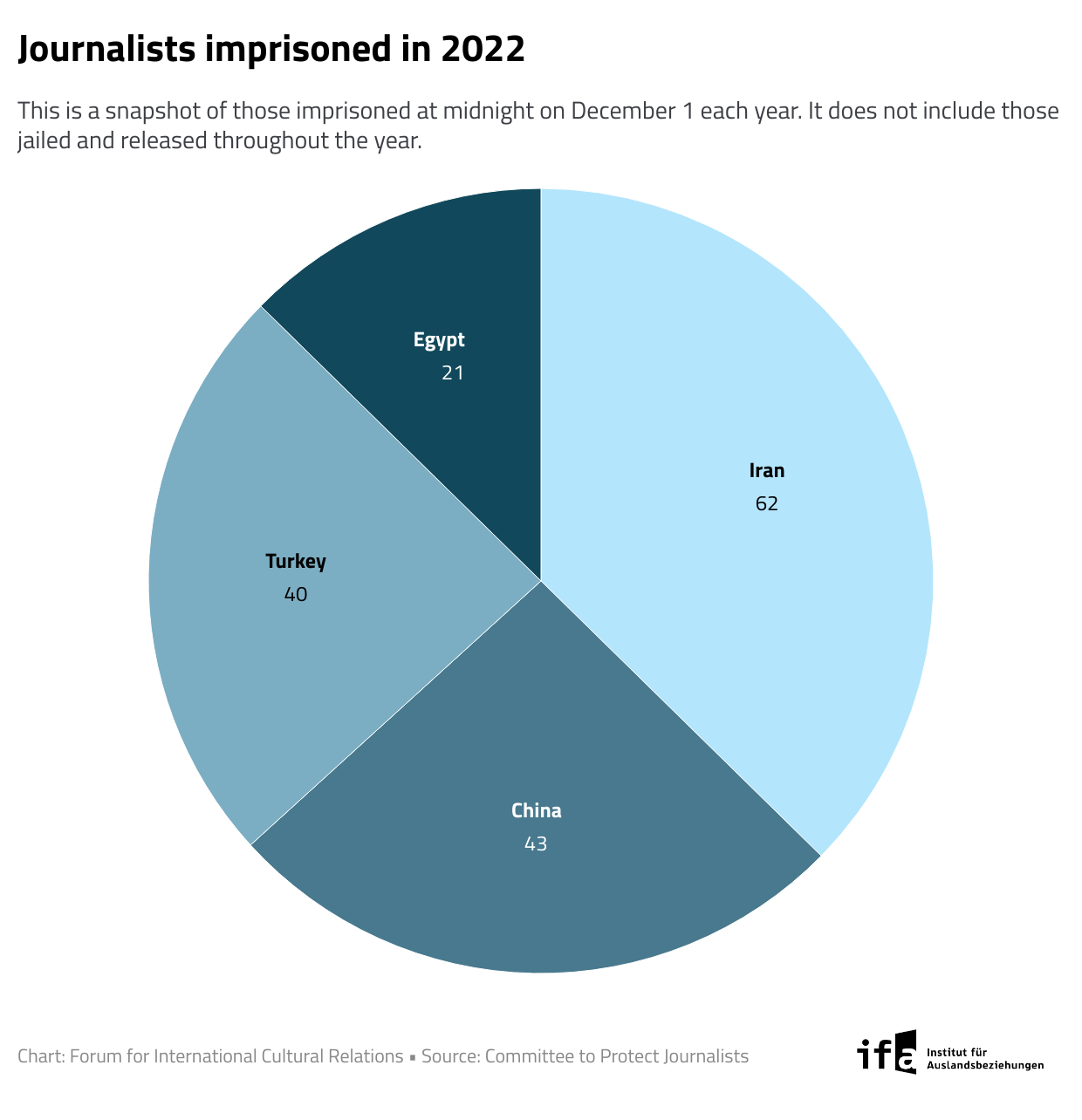

Across the world, journalists often bear the brunt of official policies to silence criticism and gag independent voices. In 2018, the Committee to Protect Journalists reports, 251 journalists were imprisoned, and 54 were killed. Turkey, China, and Egypt were responsible for more than half of those jailed around the world for the third year in a row.

Impunity for crimes against journalists remains the norm, with justice in only one in ten cases. China runs the largest and most sophisticated internet censorship operation in the world, and its big firewall is being emulated from Vietnam to Ethiopia. In many countries (including European ones), public service broadcasting is under threat and licencing of private broadcasters lacks transparency. Worldwide, respect for freedom of expression and information is at its lowest point in ten years.