As long as this set of circumstances prevails, it is difficult to see progress in the EU’s regional aspirations or posture. In other words, the EU cannot be a functional or convincing multilateral organization, it cannot meaningfully advance its core ideological and political principles, those upon which it was founded, unless it develops the mechanisms to circumvent the spoilers within its own midst. This matters both in the technical but also the broader political sense.

In the first case, it is imperative that the EU moves decisively towards a qualified majority model for dealing with its foreign and enlargement policies, especially with respect to the Western Balkans. Already, a group of nine-member states, which includes heavyweights Germany and France, has begun pushing for the same but it is vital that the matter be recognized as existential to the legitimacy of the EU as a foreign policy actor.

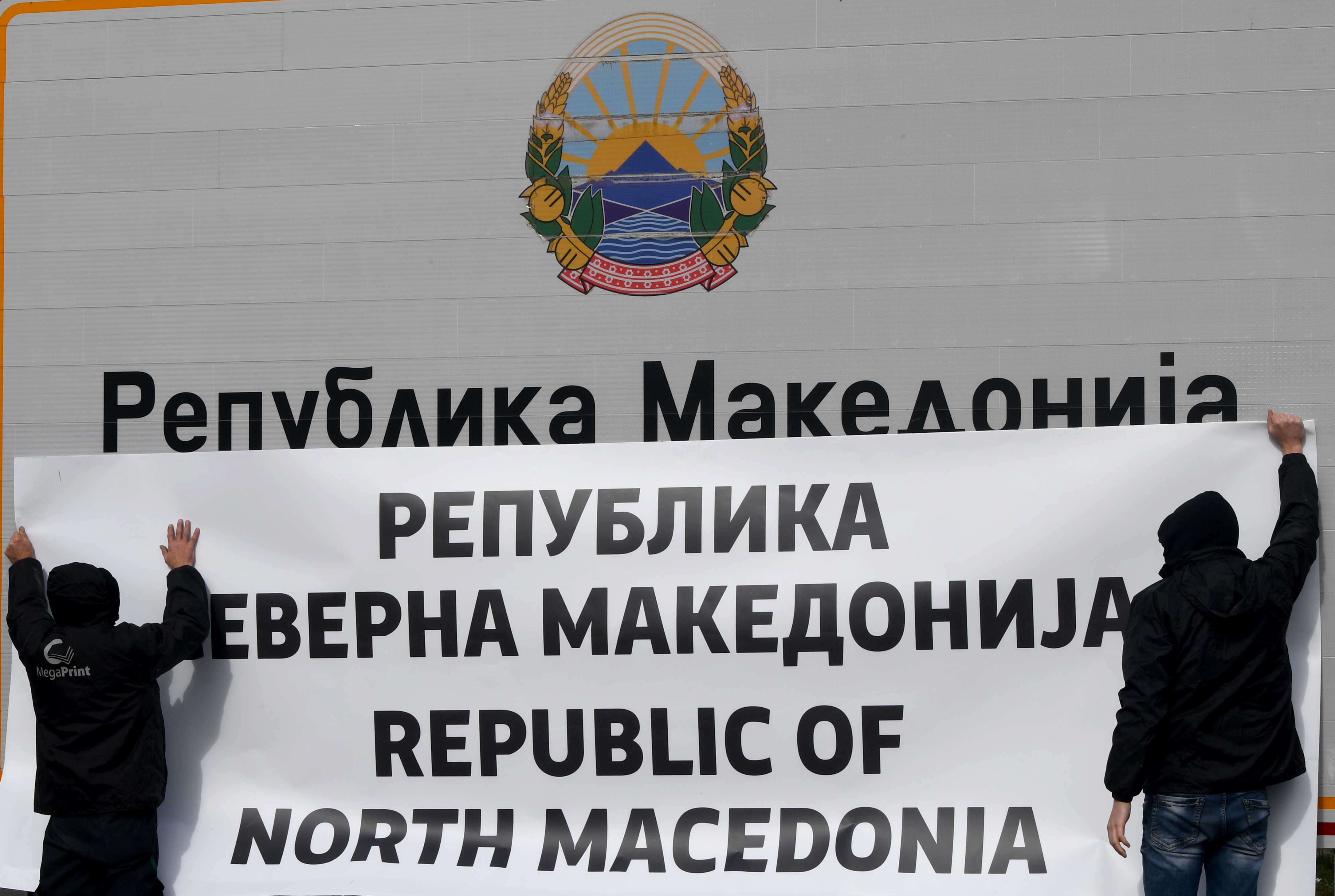

So long as states like Croatia, Hungary, and Bulgaria can completely derail the priorities of a political union of half a billion European citizens, the EU will be no more than a geopolitical imp. That is especially the case with respect to glaring inadequacies such as the Hungarian veto over EU sanctions against secessionist Dodik, but also Bulgaria’s malign blockade of North Macedonia.

It is imperative that the EU moves decisively towards a qualified majority model for dealing with its foreign and enlargement policies, especially with respect to the Western Balkans.

In the second case, the change required is more comprehensive and normative. As improbable and perhaps even dangerous as it might seem to some EU champions, it is time for the bloc to seriously reflect on its own inadequacies, and to pivot on these with respect to its Western Balkans policy. Namely, the EU is no longer able to credibly “preach” to the Western Balkans about even the most basic political principles. Berlin, for example, may want to emphasize the significance of rule of law reforms but such innovations ring hollow when it is ensconced in the same political bloc as Hungary or Poland.

France may wish to stress the necessity of dialogue and negotiation as part of the accession process but then we must recall that divided and half-occupied Cyprus is a member state. The Netherlands may champion the values of liberal democracy, but it too is in a bloc with Croatia that promotes vulgar, ethno-sectarian collectivism, utterly at odds with the European Convention on Human Rights.