The trade allowed them to purchase or exchange necessary amenities not found in the region such as spices, oil, and rice, but in recent times it is impossible to generate a surplus of local produce to trade. There is an exodus leaving Lo Mustang due to a loss of livelihood and increasing economic disparity, discrimination, and marginalization. Climate vulnerability is set to rise in the future further escalating the already dire situation, not just limited to local societies but also to its culture and heritage.

For centuries Lopa people acted as the main intermediaries in Trans-Himalayan trade but political developments in Tibet after the 1950s ended the ancient trade.

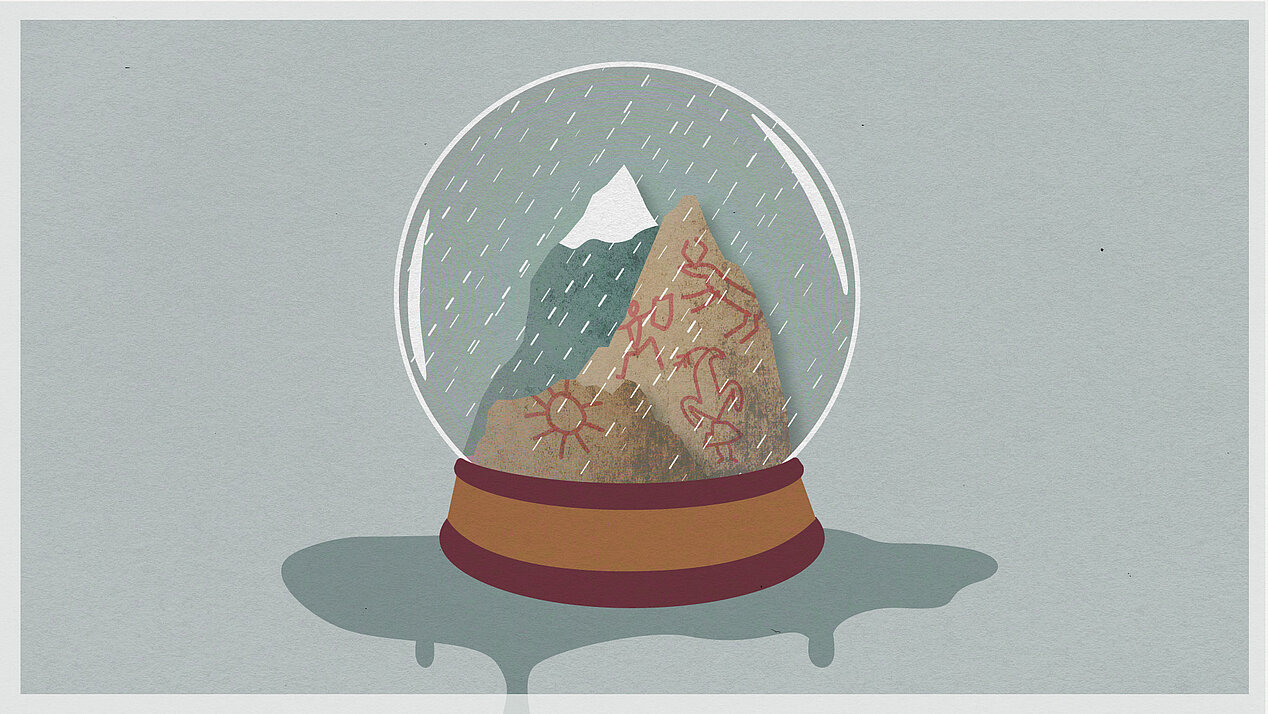

The traces of historic and prehistoric civilization are scattered around the Lo Mustang region in the caves, valleys, crags, and alongside the riverbeds, etc. since time immemorial. Environment and climate change in the present may push some of these obscure heritage sites into complete oblivion, and a part of their identity with it. Among those is a newly discovered heritage and archaeological site inside of Dhe village territory in Shar-ri, the eastern part of Lo Mustang. These sites and countless others in the region run the risk of being lost without people even realizing their importance.

The village Dhe is locally referred to simply as Dewa which signifies the concept of Sukhavatī or the blissful land of Buddha. The history and origin of Dhe are unclear and record books about Dhe or its previous settlements are almost non-existent in the public domain. However, there are well preserved oral histories in the village that provides invaluable insight into the origin and movement of the village ancestors highlighting some of the heritage sites inside the village territory and their relationship to the people and places of the region in social, cultural, and historical context.

One of the most historically important places in the Lo Mustang region is located in a rock at the lower end of the Kya Valley at an altitude of around 4200 meters. The rock is known locally as Sulledak and overlooks Mount Bhrikuti Himal (6361 meters) to the south, named after the Buddhist goddess Bhrikuti. There are huge rocks scattered around the base of the cliff. It is easily accessible, but not many villagers are aware of its existence.

There are well preserved oral histories in the village that provide insight into the origin and movement of the village ancestors highlighting some of the heritage sites inside the village territory.

The site also contains a few man-made dwellings with fireplaces and smoke deposits on the wall and ceilings. The structures may have been used by the nomads in former times, but the later dwellers most probably were hermits, whose patrons must have been the ancestors of the villagers. It is also possible that some of the later pictographs and inscriptions on the sites were made by hermits based in Kya Valley or its vicinity.

Even though almost all the paintings and inscriptions are exposed directly to the harsh environment of Lo Mustang, some are still in good condition. However, some on the lower surface of the cliffs near the soil are destroyed due to moisture and winter snow. There are only some red pigments left at the scene, visible only at the close inspection of the site. A comparative study of the photos from 2013 and 2022 shows the speed of deterioration of some of the rock paintings and inscriptions from the crag.

The unprecedented amount of rain and flooding in recent years seems to have affected some artwork. Signs of artwork close to the lower surfaces can be seen partially; in in some cases, they are completely destroyed. The Sulledak is also prone to rock fall and erosion, which has laid bare some of the artwork to the harsh Himalayan conditions and contributed to the rapid destruction of the artworks.

The unprecedented amount of rain and flooding in recent years seems to have affected some artwork.

The second site located in Kya valley is called Foradak which lies below the lower end of the Sherthang plain on the east. The site contains what look like religious inscriptions on the clay surface of the crag. The site was discovered in 2017 after a tipoff from Karsang Chödon one of the village elder now living in exile with her family. Dhe villagers didn’t know about its existence prior to that; it was long forgotten. The site consists of an abandoned pen and a small dwelling directly underneath the inscriptions site which is about two to three meters high above the ground.

I strongly believe that any modus operandi for the conservation and preservation of such sites should be based on scientific studies with a multidisciplinary approach. This is only possible when stake holders, local agencies, government(s), aid/funding organizations, and academic institutions collaborate and coordinate with each other to strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard such vulnerable cultural and natural heritage sites.

Questioning the European Commitment

Culture has always been at the heart of Europe’s identity and it contributing to prosperity, social cohesion, and the overall wellbeing of Europeans which consolidates Europe’s image and influence in the world. The European member states have focused on cultural objectives in their Social Development Goal’s (SDGs) implementation strategies and the EU leaders have also openly pledged to increase their support to global cultural cooperation.

The SGDs have given the EU an unprecedented opportunity for global cooperation in the field of culture, which also resonates with the core value of the 2005 UNESCO Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions. This Convention highlights the duty to protect and promote cultural diversity at home and abroad. As the world’s leading international donors, the EU and its member state are in a strong position to contribute to the protection and safeguarding of the cultural and heritages sites such as those found in Lo Mustang but somehow such conservation agendas seem to be not among EU’s top priorities.

Reports from Lo Mustang clearly indicate that flooding, earthquakes, extreme weather patterns, and other negative consequences of climate change pose a huge challenge to cultural and natural heritage sites in climate vulnerable areas such as the Himalayas. SDG (13) urges urgent actions to combat climate change and its impact. The International community and the EU must act to ‘preserve cultural heritage and promote cultural diversity’ which was also pledged by the member states during the 60th anniversary of the Treaties of Rome, in 2017.

The EU has the resources to strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard cultural and natural heritage sites. It can bring all the local agencies, stake holders, government(s), and academic institutions together.

The EU has the resources to strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard cultural and natural heritage sites. It can bring all the local agencies, stake holders, government(s), and academic institutions together.

It also has a legal obligation to do so but the necessary support programs for the protection and safekeeping of the cultural and natural heritage sites including from the 27 members state and the EU institutions are still difficult to find, to access, and to operate. Europe has much to contribute, and much to learn, in the time of climate change.