What "Don't Look Up" doesn't show is that there are structural reasons for the distorted media portrayal of the climate crisis. In the film, journalists are simple-minded and keen for attention. All in all, people are portrayed primarily as isolated individuals, as short-sighted, selfish, and incapable of action. There is no room for social contexts and dynamics in the movie.

That's a shame, because as entertaining as many people probably found the drama, it should leave viewers perplexed. If the reasons for inaction are in "human nature", there are hardly any levers for change.

The reasons for the lack of reporting are manifold and that is precisely why they are so stable. Probably the most important one is that the climate crisis has hardly played a role in the training of journalists so far, neither at journalism schools and traineeships, nor in studies. In contrast to the Covid crisis, where many colleagues were soon able to explain the most important key figures, climate expertise is still often only found among specialist journalists, in the science or climate departments.

Many journalists also lack a basic understanding of the natural sciences. Their view of social problems, like that of many politicians, is characterized by compromise and negotiation. From the point of view of democratic theory, this makes sense and is important.; However, the fact that there are physically non-negotiable limits to growth and economic expansion is often lost sight of.

In contrast to the Covid crisis, where many colleagues were soon able to explain the most important key figures, climate expertise is still often only found among trade journalists, in the science or climate departments.

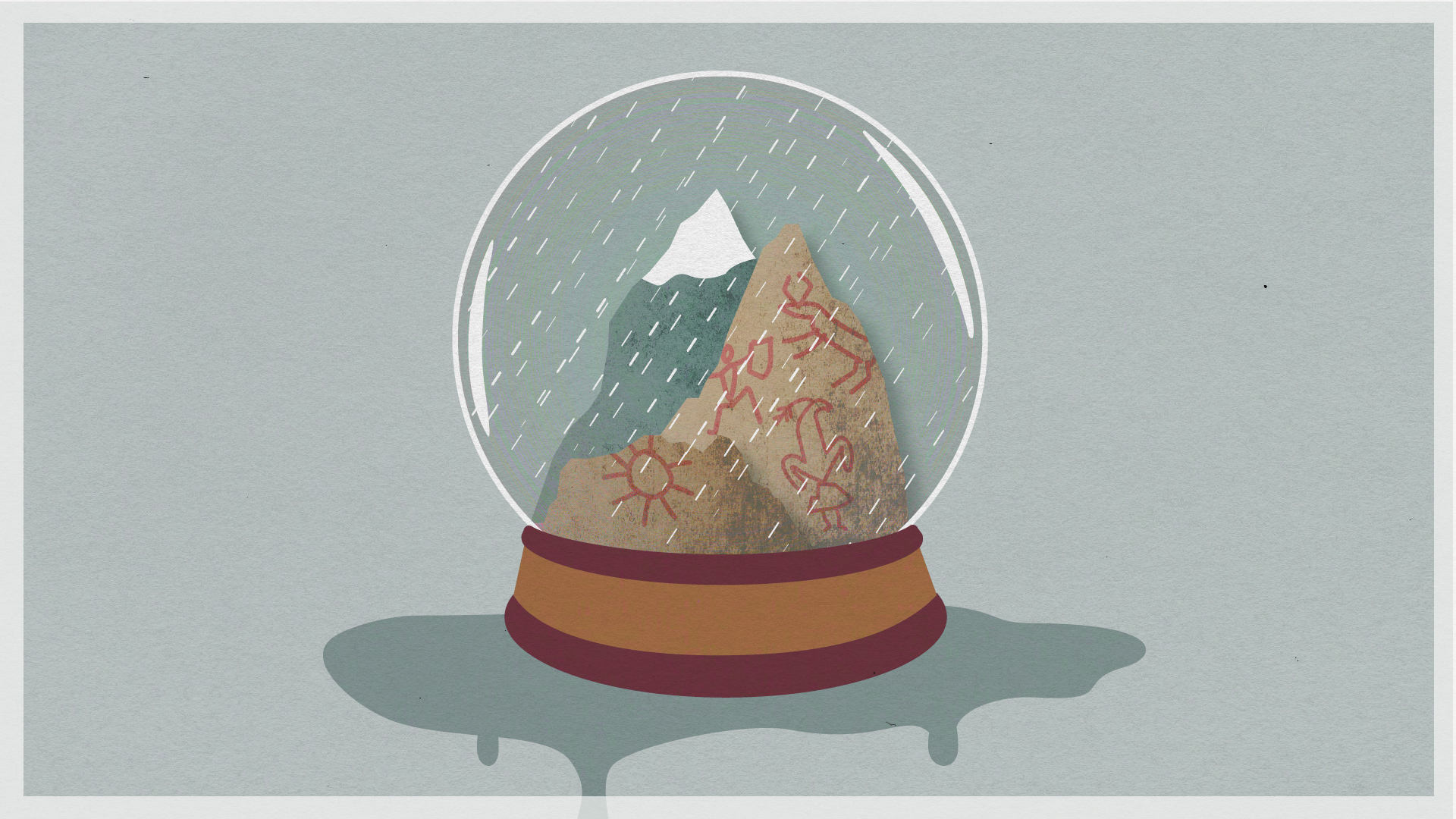

We can negotiate socially about how we want to manage to break down certain borders and stop tipping points. Or we can consciously decide not to try this in the first place and live with the consequences. At the moment politicians and economic decision-makers are postponing what is scientifically necessary and technically possible, as if inaction had no effect – as if we could negotiate with physics itself.