Prof. Mhammad Benaboud is a historian, a correspondent for the Real Academia Española in Madrid and a member of WEM as well as President of the Tetouan Asmir Association at Abdelmalek Essaâdi University.

More than other cities in Morocco, Tétouan reflects the “shared” Euro-Maghrebi-Mediterranean heritage. In 1997, the medina was included in the UNESCO World Heritage List. Because of the synthesis of Moroccan and Andalusian architecture and urban planning, UNESCO explained, Tétouan’s medina is an example of the influence of Andalusian civilisation in the Muslim west during the end of the Middle Ages. Moreover, because of the city’s strategic location on the Strait of Gibraltar, it is a link between two cultures and two continents.

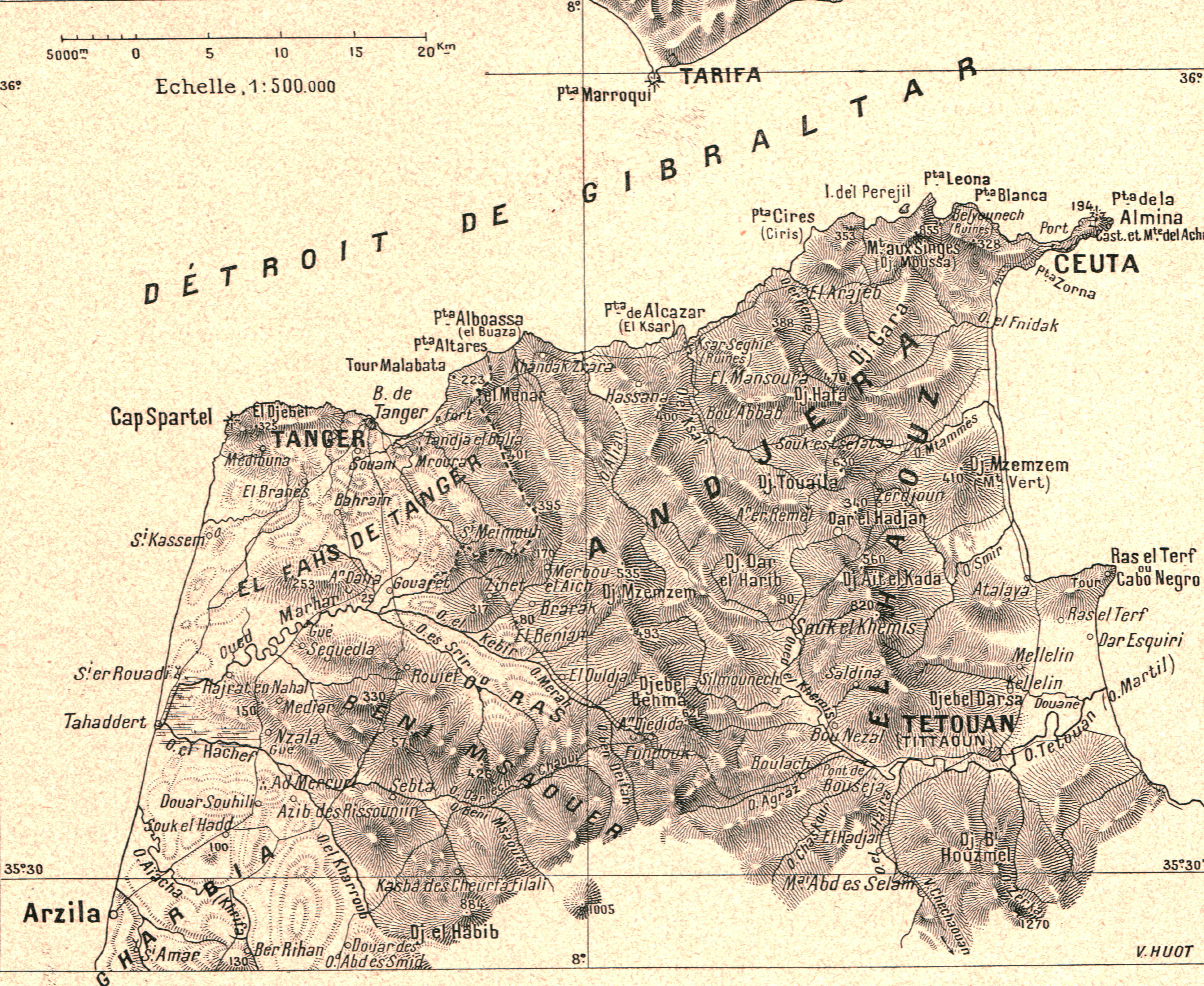

The history of today’s Tétouan begins only after the end of Muslim rule in Andalusia in 1492. The city was founded in the fifteenth century by Sidi Ali Al-Mandari. Al-Mandari had fled Granada during the Catholic Reconquista and, like many immigrants from Andalusia, settled in Tétouan. Between 1912 and 1956, Tétouan was the capital of the Spanish protectorate in northern Morocco and the Sahara. The Spanish Quarter was built as the capital, as the “capitale méditerranéenne”. The city is thus inextricably interwoven with the history of Spain, Africa and the Arab world, especially the Maghreb, of the last 500 years.

Today craftsmen work in the medina, traders sell their wares and residents and tourists stroll through the narrow streets. In spite of its status as a World Heritage Site, Tétouan’s medina is no museum. Preserving this “shared” heritage also means accepting shared responsibility. The joint restoration of the old town of Tétouan is a project that unites Morocco and Europe.

Historic monuments include the city walls, towers, the historic cemetery, streets, alleys, mosques, houses and the zaouias, or the gathering houses of brotherhoods. The Andalusian heritage is not just material; it has also left its mark on the popular music, local cuisine and traditional art.

For 25 years now, the regional government of Andalusia and its Spanish partners have been promoting restoration of Tétouan’s medina and the Ensanche, the Spanish colonial district. Many Moroccan institutions have also been restored in recent years; one such project is King Mohamed VI, begun in 2011.

There have been problems with the restoration work, in my opinion, mainly for administrative reasons. Public discourse about the historical fabric is important not only in Tétouan but in all Moroccan cities, for up to now, a strategy for the preservation of the medinas has been lacking. Administrative regulations are complex and complicated, so that only a few projects reach the implementation process. Moreover, there is a lack of coordination between the local and national levels of administration. Many administrators have no background in field research and very few of the staff responsible for the restoration projects are experts in the area. Finally, there is a lack of efficient project control. Funds cannot be raised or spent to the extent required. In some cases, the self-interest of the project partners also plays a part.

In order to make the restoration efforts in Tétouan known to European tourists as well, an architectural walk has been set up, on which visitors get to know the special features of Tétouan.

The restoration project of the association Tétouan Asmir could become a model for the preservation of other cultural heritage sites in Morocco. Since the Tétouan medina is five hundred years old, exactly five houses, one from each century, have been chosen for restoration. All the buildings were uninhabited ruins. We studied the houses thoroughly, comparing the characteristic building materials and techniques and exploring the architectural development of the medina. The houses functioned as a laboratory. We were able to reconstruct the traditional methods of making lime plaster, paints, varnishes and tiles or zellige. Tétouani ceramics were used mainly in courtyards, columns and fountains. They are characterised by their bright colours and the variety of geometric shapes. Their use was especially widespread during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. For Tétouan, characteristic elements are arches, columns, fountains and the ironwork of the shemasa, most often used in the entrances to the courtyard for better ventilation and more light.

The Andalusian heritage is not just material; it has also left its mark on the popular music, local cuisine and traditional art.

Numerous problems were associated with leaky roofs and the resulting water damage. After the roofs, the buildings themselves were restored along with the traditional water supply system, modern sanitation, electricity and telephone networks. Almost all of the materials used come from the region, so they are cheap and do not incur additional costs for transport.

Water is a precious commodity throughout all Moroccan old towns, including the medina of Tétouan. Although most of the houses are now connected to the modern drinking-water system, a look at the traditional water distribution systems will show how difficult and elaborate the restoration was. The water from the Skundo system comes from springs on Mount Dersa and flows underground in pipes of burnt clay through all quarters of the medina. The system has existed for five centuries and is very complex. All restored wells are fed with Skundo water. In one of the five houses was a matfiya, an underground cistern in which rainwater was stored. In the past, water was brought to the surface with buckets; today pumps are also used. In one of the seventeenth century houses, six bwate – large clay pots in which rainwater was collected – have been restored.

So that the restored houses are not exposed to decay again, they must be used straightaway. Today all the houses are riads, small hostels. In addition to the two to four bedrooms on the first floor, there is the reception and the cafeteria on the ground floor. This kind of restoration approach is advantageous because it not only preserves World Heritage sites, but it also simultaneously creates jobs and generates revenue through tourism. We hope that our project will be a model for similar projects in the medinas of other cities in northern Morocco such as Chefchaouen, Tangier, Larache, Ouazzane and Al Hoceima.

Prof. Mhammad Benaboud is a historian, a correspondent for the Real Academia Española in Madrid and a member of WEM as well as President of the Tetouan Asmir Association at Abdelmalek Essaâdi University.