Banishment From the Preserves of Serious Fiction

In the same spirit, I think it also needs to be asked, What is it about climate change that the mention of it should Iead to banishment from the preserves of serious fiction? And what does this tell us about culture writ large and its patterns of evasion?

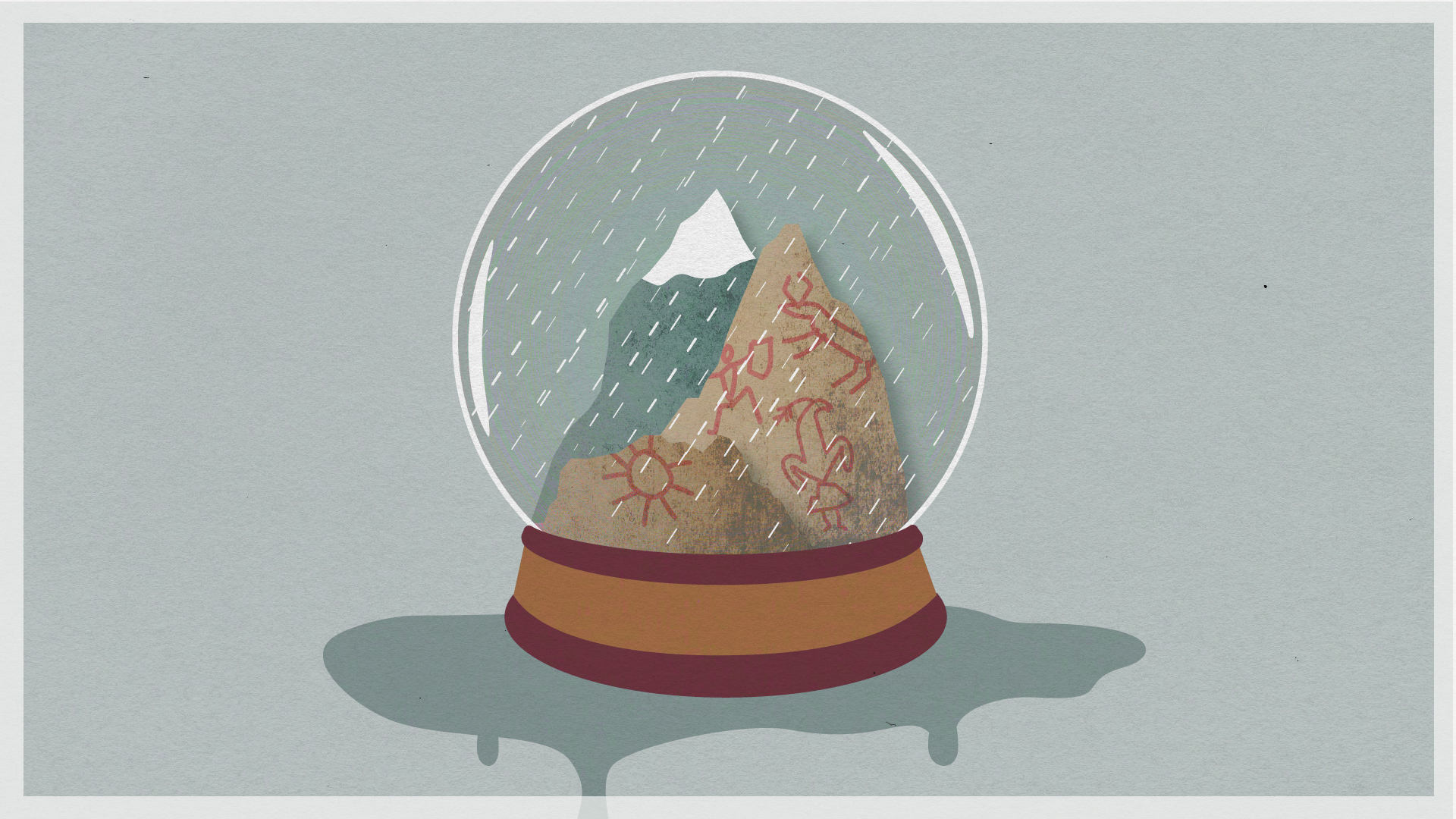

In a substantially altered world, when sea-level rise has swallowed the Sundarbans, the largest mangrove forests on earth, and made cities like Kolkata, New York, and Bangkok uninhabitable, when readers and museumgoers turn to the art and literature of our time, will they not look, first and most urgently, for traces and portents of the altered world of their inheritance?

And when they fail to find them, what should they-what can they-do other than to conclude that ours was a time when most forms of art and literature were drawn into the modes of concealment that prevented people from recognizing the realities of their plight? Quite possibly, then, this era, which so congratulates itself on its self-awareness, will come to be known as the time of the Great Derangement.

It could not, of course, be otherwise: if novels were not built upon a scaffolding of exceptional moments, writers would be faced with the Borgesian task of reproducing the world in its entirety. But the modern novel, unlike geology, has never been forced to confront the centrality of the improbable: the concealment of its scaffolding of events continues to be essential to its functioning. It is this that makes a certain kind of narrative a recognizably modern novel.

The questions that confront writers and artists today are not just those of the politics of the carbon economy; many of them have to do also with our own practices […].

Here, then, is the irony of the "realist" novel: the very gestures with which it conjures up reality are actually a concealment of the real. What this means in practice is that the calculus of probability that is deployed within the imaginary world of a novel is not the same as that which obtains outside it; this is why it is commonly said, "If this were in a novel, no one would believe it."

Within the pages of a novel an event that is only slightly improbable in real life-say, an unexpected encounter with a Iong lost childhood friend-may seem wildly unlikely: the writer will have to work hard to make it appear persuasive.If that is true of a small fluke of chance, consider how much harder a writer would have to work to set up a scene that is wildly improbable even in real life? For example, a scene in which a character is walking down a road at the precise moment when it is hit by an unheard-of weather phenomenon?

To introduce such happenings into a novel is in fact to court eviction from the mansion in which serious fiction has long been in residence; it is to risk banishment to the humbler dwellings that surround the manor house-those generic outhouses that were once known by names such as "the Gothic;' "the romance," or "the melodrama;' and have now come to be called "fantasy," "horror," and "science fiction."

The superstorm that struck New York in 2012, Hurricane Sandy, was one such highly im probable phenomenon: the ward unprecedented has perhaps never figured so often in the description of a weather event. In his fine study of Hurricane Sandy, the meteorologist Adam Sobel notes that the track of the storm, as it crashed into the east coast of the United States, was without precedent: never before bad a hurricane veered sharply westward in the mid-Atlantic. In turning, it also merged with a winter storm, thereby becoming a "mammoth hybrid" and attaining a size unprecedented in scientific memory. The storm surge that it unleashed reached a height that exceeded any in the region's recorded meteorological history.

Never before bad a hurricane veered sharply westward in the mid-Atlantic.

Indeed, Sandy was an event of such a high degree of improbability that it confounded statistical weather-prediction models. Yet dynamic models, based on the laws of physics, were able to accurately predict its trajectory as well as its impacts.

But calculations of risk, on which officials base their decisions in emergencies, are based largely on probabilities. In the case of Sandy, as Sobel shows, the essential improbability of the phenomenon led them to underestimate the threat and thus delay emergency measures.Sobel goes on to make the argument, as have many others, that human beings are intrinsically unable to prepare for rare events. But has this really been the case throughout human history? Or is it rather an aspect of the unconscious patterns of thought-or "common sense" -that gained ascendancy with a growing faith in "the regularity of bourgeois life"?

I suspect that human beings were generally catastrophists at heart until their instinctive awareness of the earth's unpredictability was gradually supplanted by a belief in uniformitarianism-a regime of ideas that was supported by scientific theories like Lyell's, and also by a range of governmental practices that were informed by statistics and probability.