Going back to my metaphor of a supermarket, what you find today in that shopping basket depends, of course, on where you are shopping. If you happen to be doing your shopping in, say, Vienna or in some other place in the “West” or “Europe” (and there are other supermarkets loaded with meanings almost to the point of bursting!) your understanding is, to put it very simply, that the Balkans is what Europe is not. Never mind geography, the frontier is somewhere in the mind more than in the landscape itself. For contemporary people, it is most likely in their memory in the form of television images from the recent wars.

The frontier is somewhere in the mind more than in the landscape itself.

If you close your eyes for a moment and say the Balkans, what comes to your mind are probably images of refugees, women with head scarves crying, the ruins of Vukovar, dead bodies, more dead bodies, Christianne Amanpour of CNN reporting from some site of tragedy and destruction.

Then, perhaps you might remember the numbers (over 7,000 Muslim men executed in Srebrenica, 60,000 women raped, 200,000 dead in Bosnia, 10,000 children wounded and so on). Or, if you don’t remember numbers, you probably still remember faces, especially that of a skeleton-like young man behind the barbed wire fence of a Serbian concentration camp in Omarska, Bosnia. Or the faces of war criminals like Ratko Mladic, a mop-headed Radoslav Karadzic or Slobodan Milosevic.

What comes to my mind, however, is a pullover, a white handmade pullover with red splotches. It belongs to the father of a little girl who was killed by shrapnel. As her father held her tiny body, her blood soaked into his pullover which he was still wearing shortly afterwards, when the CNN camera filmed him. How could you blame a person for remembering all that when hearing the name the Balkans?

Some of you will probably also remember the extraordinary blue colour of the Adriatic Sea or the fine food, or the beach with small white pebbles there, the beach you visited with your parents back in the 1960s when everything was different. But I am afraid that the idea of the Balkans as non-Europe has already become strongly re-established in the collective mind since you last visited that idyllic place.

Maria Todorova’s book ‘Imagining the Balkans’ has made people even more aware of the “imaginary geography” we are dealing with here […].”

The Balkans is far from being merely a name. Maria Todorova’s book ‘Imagining the Balkans’ has made people even more aware of the “imaginary geography” we are dealing with here, to use Edward Said’s expression. To refresh our memory, Todorova points out that the Balkans is an old name (the Turkish name for the Stara Planina mountain in Bulgaria) but a rather new expression, dating from the end of the 19th century. Then, in a kind of “literary colonization,” the Balkans slowly became a dark, dangerous but also exotic place.

This happened thanks to various Western writers, from Bram Stoker and Karl May to Rebecca West and Agatha Christie, I might add, all the way to the postwar memoires of politicians like David Owen and Richard Holbrooke or the “travel” books of Robert Kaplan and Peter Handke. The Balkans became a space where mythology rules history, inhabited by wild and exotic people to whom blood and belonging are the most important values, where conflicts and religious wars are forever looming overhead in this space of insecurity.

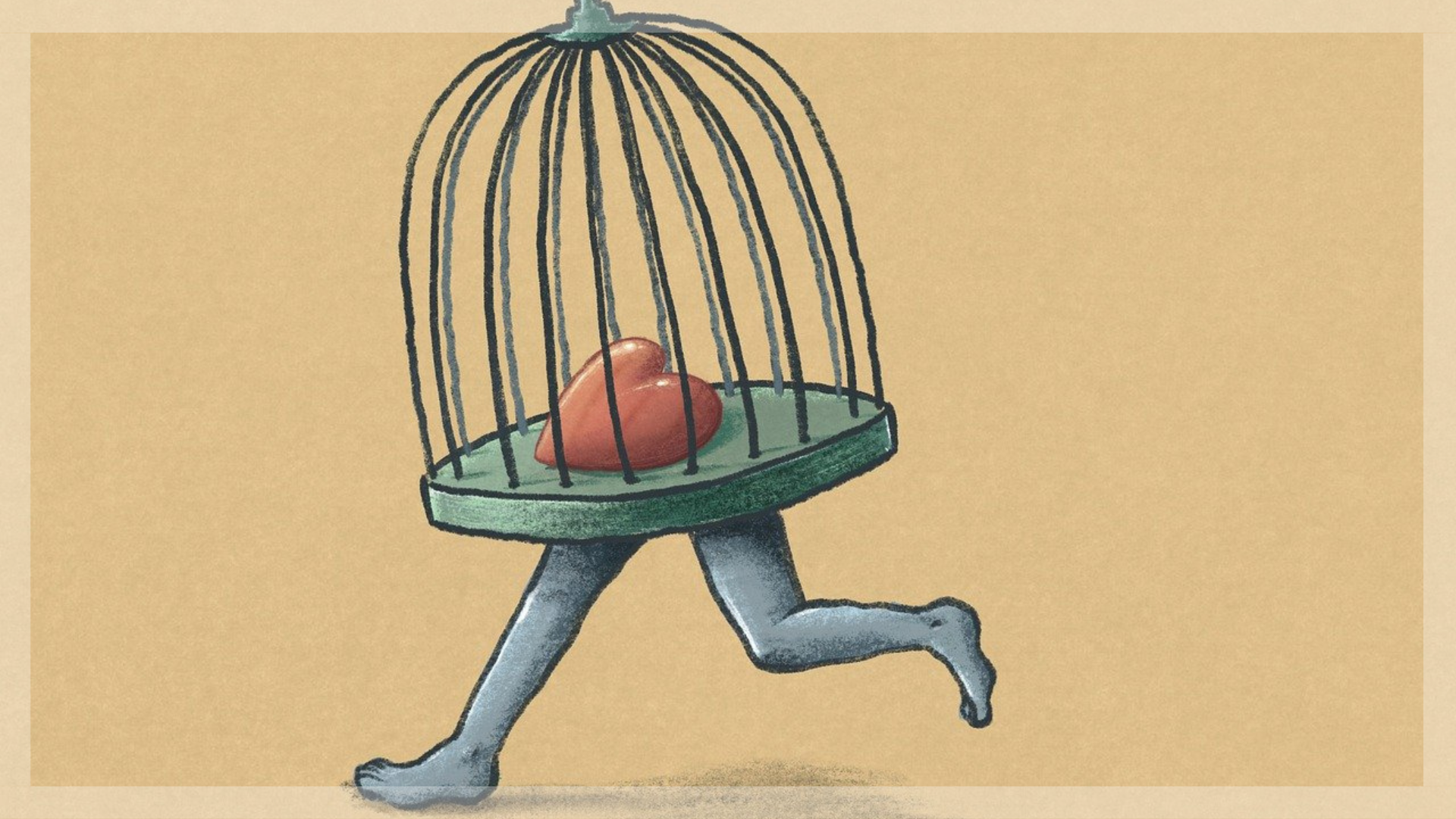

Of course, as a consequence, people inhabiting this space-name-verb-image-symbol-landscape became prisoners of the negative connotations themselves. They (we) do not like to belong there and therefore we try to get out of where we don’t want to belong. Looking at it from what one would consider an inside view of the Balkans, it looks different: “The Balkans – that’s the others!” as Rastko Mocnik, a Slovene sociologist, expressed it in his ingenious paraphrase.

And consequently, each of us, Slovenes, Croats, Serbs and so on, look further East for the Balkans as this symbolic/imaginary border moves from Vienna’s Landstraße to Trieste and Ljubljana, then to Zagreb and Sarajevo and then to Belgrade and even more southeast to Pristina. No border in this world is so flexible because it is not so much a border as a perception.